Text and photographs by Evi Lemberger1.

“Home is a Nonplace. Home is an utopia. You can experience in the most intense way, if you are away and you miss it; the actual homefeeling is the homesickness. And even if you are not away, the homefeeling nourishes itself out of the missing, out of that, which does not anymore or not just yet exist. Because the memory and the longing are turning places into homes.”

Transcarpathia

Transcarpathia is a region in the west of Ukraine, surrounded by the natural border of the Carpathian mountains and the artificial borders of the countries Hungary, Slovakia and Romania.

In the past it seemed to be a political football. Within the 20th century it used to belong to 7 different countries; till 1918 it belonged to Hungary, then for 20 years to Czechoslovakia, for two weeks it became an autonomous republic, then, till 1944, to Hungary, then to the Soviet Union and since 1991 to Ukraine. Nowadays the region is highly multicultural and mixed; sixteen different nationalities are living in this area.

The main spoken languages are Hungarian, Ukraine, Russian, Romanian, Polish, German and other small spread-out languages or dialects. The official language is Ukraine but most of the inhabitants of this area can’t speak or understand it. There are minority laws which protect their rights, but in terms of language there is a tendency to force them to speak Ukraine, which leads to numerous problems, not just on the practical but also on the personal level.

Politically and economically the area tends to be dismissed by the governments of both Ukraine and Hungary. The area statistically has about 80 to 90 percent unemployment. In reality people have their job but mostly the payment is so low that the people are forced to have two jobs and also have some fields and animals in order get their own food. Opinions about the government are quite similar within different social and nationality groups. They do not feel supported by the state and have little political influence.

Religion and church also play a highly important part of everyday life, either as a financial and administrative support (the church mostly funds institutions such as elderly homes, orphanages and gypsy schools) or as an identification model (which was very visible after the collapse of the Soviet Union; increasing numbers of people joining a religion). The result is a high membership of different religions, such as Roman or Greek Catholic, Reformist, Greek Orthodox and other numerous small sects.

On a social scale people live peacefully together. Although having sometimes 16 different nationalities and numerous religions in one city. Interaction between the different nationalities depends on the multiculturalism in each place. Sometimes it happens that people live together but have almost no connection on a social level, as in Bergegsász, where mostly Hungarians are living. In the highly multicultural town Técsö, a new language has developed, which is a mix between Ukrainian, Russian and Hungarian. One odd outcome of this multiculturalism is the setting of time. Depending on the inhabitants and the size of the village, the time is set to Hungarian or Ukrainian time (Hungarian time, the unofficial time, is one hour behind Ukrainian time).

The Project

I got interested in this area and its people, because it shows the effects of politics on a social scale. This area seems to be a football for the political leadership, in the past, because of the political changes, and now, because of the seeming lack of political presence.

The situation is typical for a lot of countries, above all in East Europe where countries were split up in the course of political changes and decisions. The result was new countries, connected not because of the similarity in language, history or culture but rather because of geographical aspects. The result is an artificial group of people who are forced to join the same government with certain rules and legislation. Thereby nobody asked them.

So, I am wondering from where they draw their identity. Usually people have a strong relationship to their nation or to personal or professional development. Lacking both aspects, I am wondering where those inhabitants draw their influences from and what it says about the issue of identity in general.

Looking at them, I wanted not only to draw a picture of the area, and make people aware of the situation, but also to question the importance of national identity.

Travelling preparation

With the help of the organization Hilfsverein Unterkarpathen and comissioned by Norfolk Contemporary Art Society, I planned my trip to Transcarpathia for the four weeks from 15 March till 14 of April, 2009, when I visited 6 different place: Dobrony, Técsö, Koenigsfeld, Beregszázs, Vári, Lopukhovo (the names are mostly the Hungarian version).

I was staying in different places with the help of either the reformative church or local people. I always had a local translator, who helped me with interviewing people in order to find out more about the issues around their identity. The people had different nationality, religious, geographical and educational backgrounds. At the same time I was visiting official institutions like the church, school, kindergarten, old people’s homes or the town hall in order to draw a picture of the region.

Outcome

The result of my interviews, visual and academic research is a very personal interpretation; very personal because of a lack of emotional identification and experience.

People, who have a lack of national identity, for either historical or contemporary reasons (because of the lack of state presence), and who are also limited in their personal and professional development, draw themselves back into their personal surroundings: the home and the family.

The youngsters still have dreams, they want to become “a super star”, “go abroad” or “have a lot of money”. As soon as they get older the youngsters lose their dreams. Responsibility for that seems to rest on the one hand with the adults, who disillusion their dreams, and on the other hand because of their own experiences.

“I applied two times for the visa to England. I fulfilled all requirements, but they (the visa office) refused my application with the reason they do not have enough assurance I would come back… anyway I got refused and at the beginning I was very sad but then I thought: maybe instead of that I should concentrate on my house and my future family.”

This shift in aims is natural in all generations, but significant within this specific society is the extremity of both aims. When they are young they have mostly dreams, which hardly can happen in reality, at the end, shortly after becoming adult the dreams are mostly reduced to very simply aims, such as family, kids, house.

Morley also argues that,

“Driven by a sense of powerlessness in the spheres of work, politics and public life, people have retreated into a ‘spheres of autonomy and control which would restore to them a sense of identity, attachment and belonging’- in a ‘place of their own’ especially in the case of home owners.” (p. 25, Morley)

Graham D. Rowel also states in his book, Home and Identity in the late life. International perspective:

“Home permeates society, and evokes such feelings as belonging, control, comfort, or security whether it involves individuals or much larger groups of people….” ( p. 197)

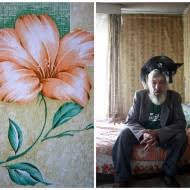

Looking at the area and the houses and in particular the interiors, the house as a space for identification becomes visible. The streets and the public places are mostly plain, dull and seem to be neglected. The streets are broken, the landscape outside the town or in abandoned places is full of rubbish and the house walls are gray and dull.

By contrast, the inside of the houses are carefully considered and all the houses show the same interest. The wall of the interior are mostly painted in strong colors. This choice depends on the household and the personal preferences, which differ according to their age and their status. Older houses have mostly prints on top of more light-colored walls, younger homes have very strong colors, where pink is at the moment in fashion. The interest in color can go so far that it can happen that each room of a house has a different color (where the color of the furniture matches the color of the walls and the curtains) and it goes from yellow, to red to green to violet. The people in this area used to change their wall color every year, a tradition which is practiced between different social groups which vary in geographical location, nationality and religion.

One reason for focusing on the wall colors could be the historical aspect of having a lack of consumer goods and money. The people, when asked for the reason for those strong colors couldn’t answer and it seems that it is completely embedded in their culture and everyday life.

This identification through colors seems to be already important in the past. Artists such as Kandinski or Emil Nolde, who painted their interiors in “deep red“ or “sunny yellow“ or political groups like the German group “Cobra 1948”, who fought with the slogan “Farbe an die Macht” (color in charge) (Turn 2007, p. 30, 31), but finally in the mid 20th century the middle class started with painting in colors and Hans Peter Turn, the author of the book Farbwirkung, Soziologie der Farbe (Color Effect, Sociology of the Color) ascribed to the emotional expression of the people.

In terms of identification the use of colors seems to involve a desire to live their personal dream, or to compensate for their dream, which can’t be fulfilled and which got lost by getting older.

Schlink argues:

“The memory turns the place into a home, in remembrance of previous and lost things, or the longing for things which are previous or lost, even the previous or lost longings. Home is a place, not that one, which he is, but this one, which he not is“ (p. 33 Schlink)

Another aspect of identity is quite visible within this area; the importance of the children. Depending on the area and the family background the number of children depends on the household.

Children, as many inhabitants there say, are not just on a practical level useful (children are important for the work in the field but also in order to care for the parents when they are older), but moreover important for the inhabitants to give them meaning in life. This becomes also clear by talking to the people, who either have this opinion or show their love for their children by talking about them, or looking at their space, which is mostly full of photographs.

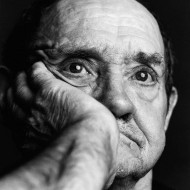

Interestingly the children are the only people who wear colorful clothes. As the people are getting older their clothes colors are getting plainer till, after the death of the husband or wife, the remaining person traditionally wears only black. It seems that the color stands as a metaphor for desire and dreams, which are still in the youngsters until they got lost and compensated for within the home.

Photographs

The resulting pictures are a very personal interpretation of the region and its issue. Those shown in the exhibition deliver a short version of my interpretation. Visually focusing on very structural and drawn back images of the interior and portraits, I wanted to underline my interpretation and emotional relationship to the people and the situation. The interiors represent the people’s desire to find their identity and their world in their home. By having very clear and structured interiors the fictional side of my interest should be underlined, through the numerous places which seem to be almost different and yet connected by the differently colored walls, their common desire of identification through their homes becomes clear, which is supported by using captions. The portraits take on the representation of a lifeline by showing inhabitants, who vary in age. The color of their clothes stands symbolically for their dreams. The portraits, which are mainly outside, stand in opposition to the very clear, almost fictional interiors.

References

- Andruchowytsch, J. , Stasiuk, A. (2004): Mein Europa. Frankfurt am Main: Edition suhrkamp

- Baumann, Z. (2004): Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Genov, N. ed. (2004): Ethnic Relations in South Eastern Europe. Problems of social Inclusion and Exclusion. Münster: Lit

- Glatz, F. Hrsg. (2003): Die Sprache und die kleinen Nationen Ostmitteleuropas. Band 21. Budapest: Europa Institut Budapest

- Moosmann, E. Hrsg. (1980): Heimat. Sehnsucht nach Identitaet. Berlin: Aesthetik und Kommunikationsverlag

- Migdal, J. S. ed. (2004): Boundaries and Belonging. States and Societies in the Struggle Identities and Local Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge

- Morley, D. (2000): Home, Territorries. Medie, Mobility and Identity. Routledge

- Rowles, D. PhD; Chaudhury, H. PhD ( 2005): Home and identity in the late life. International perspective. New York: Springer Publishing Company

- Schlink, B. ( 2000): Heimat als Utopie. Frankfurth am Main: edition Suhrkamp

- Turn, H. P. (2007): Farbwirkung, Soziologie der Farbe. Berlin: DuMont Verlag

- Zehetmair, H. Und Zöpfl, H. (1989). Heimat heute. Rosenheim: rosenheimer

Please visit Evi Lemberger website for more photos and informations.

- This work have been realized with help of Norfolk contemporary art society. [↩]

The pictures seem to be shot in places like Germany, Russia, Turkey… Interesting place.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.