Text and photos by Julianne Nash.

I began working on the series “Unseeing” over three years ago. This body of work is simply just a visual artist attempting to understand what it would be like to completely lose ones vision, ones major tool of communication, love and passion.

I can recall a distinct moment in time, while sitting across the room from my grandmother many years ago, and becoming infuriated with her for continually asking me the exact same question within a moments time. Given, I was preoccupied with something I was reading and simply just nodded my head “yes” to her question. Little did I know, her macular degeneration had progressed so rapidly, that my head motion was simply a blur to her. She could not decipher my visual accreditation to her statement, rather presumed that I was simply ignoring her.

As a young girl, my grandmother assisted my single mother in raising my siblings and myself a great deal. Seeing the woman, of whom I never thought would approach her own mortality, unable to decipher my facial features from less than five feet away was traumatizing for a teenage artist. My initial response was to take as many images of her and my grandfather as I possibly could while they were still gracing me with there presence. I chronicled their home, and their life as much as I possibly could. I spent many weekends of my college career, skipping the fun parties, and sleeping over their house, in hopes of finding something indicative of their new life.

However, with the progression of this project, my own “Catholic guilt” set in; I felt responsible for being able to see. I was scared of flaunting my ability to see to her, by creating images of her. I was extremely hesitant to offend her in any way. I began visiting for days at a time, and leaving with more unexposed film than ever before. I grew uncomfortable behind my ground glass in their home, because I started to register our shared mortality.

Macular Degeneration is a inherent condition. Meaning, there is a large chance that I will slowly lose my vision, too.

Nan Goldin once said:

“I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough.

In fact, my pictures show me how much I’ve lost”.

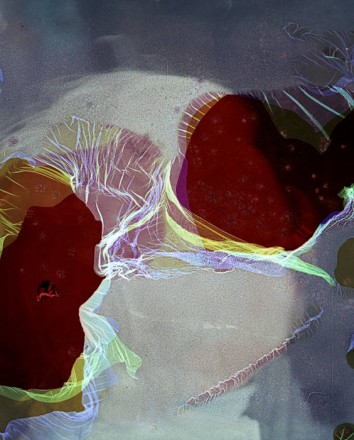

This is essentially why I begun to physically degrade my negatives; in oder to somehow absolve myself of the guilt I felt being able to experience the world, and to battle with my own fears of absolute darkness. I compiled a stack of over 20 negatives that I cherished of my grandparents; images of us together, of adoring glances, and of treasures within the home. I doused them in bleach, cleaning solutions, salt and sugar, boiled them, burnt them—destroyed them in every way I could think of. In my own freaky way, this helped. I was able to understand the loss my grandmother was experiencing an a very personal manner; and was able to diminish my anxiety over losing myself, too.

With that, I broke barriers within my own photographic process, and was capable of creating much different work. I stopped fearing the camera, and it’s ability to render the seen and unseen. I took advantage of it.

First off, I began to make many images using a simple pinhole camera. I was interested in breaking down my visual elements to it’s purest form—abstract color and shapes. I decided to place the pinholes in front of the moments in life that I cherish the most: sunsets/sunrises, snowstorms, stargazing, ect. The results were essentially the most abstract form visual relation I could accomplish at that time. Essentially, I was creating images that my grandmother could also enjoy. There were not details that she missed, or spots of darkness obscuring focus—they were simple enough for her to also enjoy.

Within that year, I also created a few large format 20×24” Polaroid images that further articulated my idea. The two most successful images were plays upon the idea of a “self portrait”, but through the eyes of my grandmother looking upon me…

For the first image I combined my mother’s face with my own. My grandmother has been confusing our faces from across the room ever since I hit puberty — and, to her benefit, we have strikingly similar features. Essentially, I covered half of the lens and exposed my mothers face on the film, processed it, retracted it and exposed half of my face on the opposing side. To the naked eye, there is confusion upon seeing it because our skin tones are deceivingly seamless.

For the second image, I wanted to destroy an image of myself. Much like the degradation of my physical negatives, I chose to degrade my “one of a kind” 20×24 polaroid image, by creating a transfer print. To accomplish this, I over exposed my negative (in order to have enough sustenance to the negative to be able to remove the emulsion), and placed the emulsion upon a damp sheet of coarse watercolor paper. I used a printmaking roller to essentially “push” the emulsion off of the negative and onto the paper. The results are an almost terrifyingly obscure view of my face; seemingly melting and disappearing from the paper itself.

My hope with this work has always been apathetic. I have always wanted to bring light upon the fear of macular degeneration, in my own extremely personal way. I have always wished that the viewer would immerse themselves in the abstract images and question what they are actually looking at: to feel as if they are inside of a retina, or to understand the physicality of the “dryness” in her eyes everyday; or, to just feel, as an able viewer, to understand another’s struggles.

And, most importantly, I wanted to pay homage to a woman I love and respect. To bring honor to her, for all that she has accomplished, and all that she will accomplish in her final days of coping with her sightless condition.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.