If you’ve ever been to China you should know how Chinese are crazy about photography. It’s not just a stereotype depicting Chinese tourists in Europe snapping thousands of photos in a day; it is the truth.

It’s a fact that photography often happens while traveling, especially when abroad. It is not a case that the photography market in China exploded right after the middle-class reached the possibility to visit foreign countries. When in the late 20th century the Korean and Japanese tourists floods overwhelmed Europe, we were amused by the thousands of photos they were able to shoot in a day; nowadays we are surprised by the number of cameras and lenses Chinese tourists can bring along with them. There are some differences. Japanese tourists have usually a more introspective approach to their photos, they are mostly shooting at themselves, and this is why they prefer compact cameras. Their Chinese counterparts live instead photography as a tool for ‘sharing’ their experiences within their circle and community, this is why besides the status symbol of owning the flagship camera of the range, Chinese choose (D)SLR cameras: it adds value to the photos they share. In this Chinese tend to show the behavior of a social collective mind.

In my college years in Tsinghua I was amused by the number of SLR cameras my classmates had, all of which costed at least twice the country’s average per capita income. With my 400 euros Olympus I was their joke. A few years back a meme appeared on the Internet: “摄影穷三代,单反毁一生” literally “third poor photographers generation, reflex cameras ruin lives”, and a photo of a beggar-looking middle aged man looking into the viewfinder of his expensive camera. These memes testify a real passion Chinese share about photography, and how they wish to spend a lot of their income in order to purchase professional cameras with good lenses.

The average Chinese amateur photographer strives to reach formal perfection. Blurred images, which are common in fields such as street photography, are not easily recognized as good shots in China, even tough they might be very expressive. This is also a reason why the average middle-class photographer alway tries to buy the best lenses and the best accessories.

I have been wondering for a while now at why is photography such a big thing in China and I came to the conclusion that since China is a fast changing country, people feel the need to fix their memories and stop for a bit the impetuous flow of time. Without time for reflecting, only with the dry sound of the shutter mirror. And this must be the reason behind the huge request for wedding photography in China. The 798 art district, the Shichahai Lake, parks like the one of the Summer Palace or Beihai, kitsch architectures like the european style Chateau Changyu, are among the most popular backgrounds of beijingers’ wedding shots. In the past thirty years the working and living pace has been growing faster and faster, and with speed a sense of precariousness comes along.

Everything is fading away. In Chinese mega-cities friends move in and move out, most of the young Chinese must themselves often relocate for college, far from their parents and childhood friends, and then most likely move again after graduation. Here comes the need to stop the time flow. Back in 2011 while I was doing a workshop with some students from Swiss EPFL in 798, Beijing, (here andhere) to understand people’s behavior within that area I had to conduct a small series of interviews to some couples that were going to marry and have a wedding photo-shooting in there. All the couples I interviewed stated that they wanted to keep a memory of their youth. Of course, this is the reason behind beauty and wedding photography in every culture, but the proportion of the phenomenon in China has reached a proportion that is well described by LVMH, the world’s biggest luxury goods conglomerate, investing in a Chinese wedding photography company.

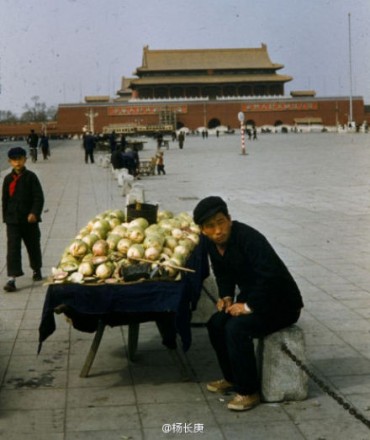

When everything changes so fast photos can be reminiscent of a long forgotten past. This is what happened when an old color photo of Tiananmen Square was uploaded to Weibo, a Chinese Twitter-alike social platform. This is why many Chinese photographers felt the moral duty to go to the countryside and capture the last faces of a rapidly disappearing rural China.

But besides the need for recording today’s memories, in a country where pollution, savage industrialization and wild urbanization are threatening the concept of beauty, there is also the need to (re)create a forgotten beauty. Like in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities Marco Polo says (quite ironic isn’t it), “The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space”. This second way can be pursued through the lens of a camera, leaving all the daily ugliness outside, while only keeping what fits the viewfinder, maybe further improving it through postproduction.

Chinese leaders have always put a big emphasis on photo retouching, from Mao’s era to the 18th National Party Congress, and so do Chinese youngsters. The market for selfie-retouching apps has grown so big that real-life make-up companies have started to market themselves after them. If life is memories and we rely on photos to remember, photography can be a powerful tool to dramatically change our lives.

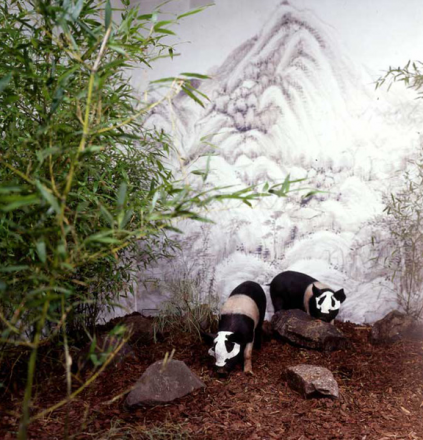

All this can be real fun, but sometimes reality suddenly comes back, slammed on our faces, and photography can still be there, reminding us not to believe what we see at first glance, but to dig deeper. The panda-looking pigs of Xu Bing’s Panda Zoo (熊猫动物园, 1998. 徐冰) and the Chinese-traditional-landscape-looking trash of Yao Lu’s New Landscapes are here to remind us that everything is a mere illusion, but we must cope with that.

You can find a shorter version of this article on Michele Galeotto blog.

A lot of Chinese people like more and more to show off. Having an expensive camera is one way to do so. I’ve been in China for many years and I’ve seen a lot and a lot of people buying the last model of a brand (mostly Nikon and Canon) and using it always in auto mode. When I was shooting digital and looking at my pics with the histogram, I’ve met many photographer asking what I was doing. If you shoot analog, medium format for example, you’ll see old people, with a camera or not, coming to you and talking (when you speak chinese) with you about the time when they use to shoot analog too (one more good reason to learn chinese. Living in China is reason enough to learn chinese : ) anyway…). So I won’t say that Chinese love photography because one can see a lot of Chinese with camera. Most of the Chinese that you can see travelling use their camera in auto mode and they got “the best one” because it’s something in the Chinese culture to show off. Of course, there’s some people who are different from what I’ve described. About the “摄影穷三代,单反毁一生” the guy doesn’t look loke a beggar at all. Look at his clothes : clean, modern. His shoes and trousers are new, like the camera bag.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.