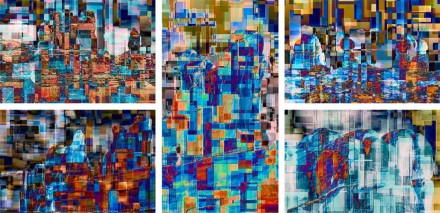

Marco Annaratone and Hanni Cerutti

Text and photos by Twelve-Tone Photography.

Sometime the production of artwork follows convoluted if not downright bizarre paths. This is the recount of one such artwork, that we have organized as a four-stage process, because it developed and reached completion in four distinct phases over a period of six years.

Phase 1 – The Subject

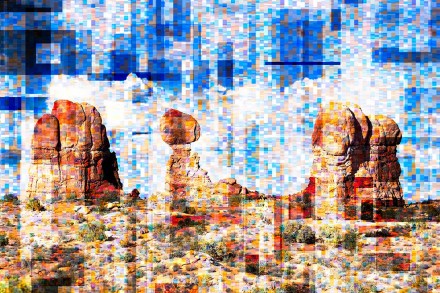

All our visits to the American South-West were profoundly emotional. We have lived for almost two decades in the US and this gave us the opportunity to explore the area in some depth. We have seen it at different times of the year: from the searing hot August days in the pink sand dunes of Yuma to the blooming season in Death Valley. The American South-West is all but a monolithic visual experience: Monument Valley and Moab, or Bryce Canyon and the Valley of the Gods, have little in common from a sensory perception. In spite of these significantly different sceneries they all impressed upon us similar emotions: a fundamental sense of disorientation, vertigo, lack of mooring, a compass gone wild. Mind you, this experience was not unsettling, it felt like a suspension of time and peaceful relinquishing of one’s comfort zone.

One particular place was instrumental in making us feel this way. The first time that we visited the Valley of the Gods these emotions overwhelmed us. This is a place out of the classical tourist routes — one can be alone there, and we mean totally alone, with the surroundings. Afterwards we were able to experience the same sensations elsewhere as well, although in a less dramatic way. Once this “symphonic fortissimo” was played for us in the Valley of the Gods we were able to experience it — although at a lower volume — in the Grand Canyon, in Moab, or Bryce.

Of course we took lots of pictures, but later we were not totally satisfied: looking at them did not evoke the same sensory experience. The disorientation, vertigo, suspension of time, lack of mooring were simply not there. The pictures were silent. Yes, they faithfully depicted what we had seen but did not resonate.

Phase 2 – The Intuition

We share a passion for contemporary classical music. It all started in our college years when we were living in Milan, Italy. At the time the city, in cooperation with the local Music Academy, was organising yearly concerts as part of a program entitled “Music in Our Times” (MiOT). For several years the program offered concerts of all the major contemporary composers, from Stockhausen to Berio, from Penderecki to Ligeti. Some attention was also given to American composers out of the classical mainstream: first of all Cage, who gave a memorable performance, but also Steve Reich and Terry Riley. These concerts were the spark that set in motion our personal journey through contemporary classical music: we attended workshops in computer music at CNUCE in Pisa (Boulez’ IRCAM in Paris opened shortly thereafter), became familiar with minimalism, and even visited some musicians whose music impressed us. We still remember a young Gavin Bryars opening the door of his London flat and looking both puzzled and amused at this couple of Italian students telling him how much they loved his “Sinking of the Titanic.”

Our love for contemporary music made us think in recent years about the reasons why some parameters are kept invariant in artistic expression, often for no reason other than tradition. We asked ourselves what would happened in photography if one denied this invariance, the consequences one had to face and what could be found at the end of the tunnel that one enters when these invariances are simply made variable. Our natural point of reference was atonal music. The destruction of the invariance of tonality that contemporary music produced from Schönberg onward has been a driving force of much classical music (albeit not all) of the last century. Much could be said about it — there is an extensive literature on this topic — but one thing is certain: the jury is still out. What has happened in the 20th century may turn out to be — once filtered by time — nothing more that a cataclysmic event in the progression of musical development that has left traces — more or less profound — but few memorable compositions. Conversely, it may leave lots of masterpieces that audiences worldwide will enjoy listening to for centuries to come. Steve Reich seems to believe in the former outcome, when he says:

The reality of cadence to a key or modal center is basic in all the music of the world (Western and non Western). This reality is also related to the primacy of the intervals of the fifth, fourth, and octave in all the world’s music as well as in the physical acoustics of sound. Similarly for the regular rhythmic pulse. Any theory of music that eliminates these realities is doomed to a marginal role in the music of the world. The postman will never whistle Schönberg. This does not mean Schönberg was not a great composer — clearly he was. It does mean that his music (and the music like his) wlll always inhabit a sort of “dark little corner” off by itself in the history of all the world’s music.1

Whether atonal music will inhabit a dark little corner in the history of world’s music is outside the scope of this article and we certainly do not have the competence to provide any significant contribution to the topic. This notwithstanding, we became curious about the similarity to photography, now that digital photography (remember computer music?) has potentially broken some technical constraints. There are two major invariants in photography: color temperature and exposure. They are kept constant across the whole image field. We have found our “musical key,” therefore, and applied it to photography. The next step was to ask ourselves what would happen if we made both be variable. We expect many agree about the invariance of color temperature, while many will strongly object when reading about the invariance of exposure. Yes, yes, we hear you saying: “and what about dodging and burning? And what about HDR?” Indeed, they change the exposure in selected places (the former) or across the whole image field (the latter). But these are tools to address (perceived) visual issues, not a methodology to free the parameter of light intensity reaching the sensitive surface from an imposed, specific initial value. We stand by our statement that dodging, burning or HDR are something else.

Phase 3 – Applying the Intuition

We called this process of imposing variability to color temperature and exposure photosequencing. While we never forgot even for a moment what Reich said above, and without having the arrogance of comparing photosequencing to atonal music, we do believe that the former will certainly occupy some (very) little dark corner. We do not think it is a new way of picture taking, nor will it ever become one. But Twelve-Tone Photography’s mission is also about carrying out visual research applied to photography, and this is one of the many experiments we performed. We discuss it here since it produced artwork and solved a specific problem at the same time, and hence it is worth reporting.

The process of modifying color temperature is rather straightforward: we considered a range from 1000K to about 14000K. In fact, the sensitivity of the eye to color temperature variation is not linear with Kelvin degrees but with mired. We therefore converted Kelvin degrees into mired and divided the latter in twelve segments. These are the twelve color filters we applied to our pictures. After much experimentation we also decided that the best shape for each filter was a rectangle. Before we tried with circles, or various irregular shapes, but the results were visually unconvincing. A similar (even simpler) process has been applied to exposure, subdividing the EV space into twelve. In this case a rectangle has also turned out to be the preferable shape.

Phase 4 – The Result

The next step was to decide where and how to apply photosequencing. This is when we focused on our project about the American South-West. The rationale behind it was quite pragmatic: we loved these places and longed for the emotions we had experienced, but as we said above the pictures did not embody them yet.

The results intrigued us. The pictures were finally resonating. The emotions we had felt on location could be at long last be felt by looking at the photographs: disorientation, mild hallucination, a crazy compass, time distortion and a sense of suspension were all there in front of us. These pictures finally spoke to us. We called this project “Deconstructing the American South-West,” for rather obvious reasons.

Photosequencing forces time into a picture by its own very characteristics, i.e., modulating exposure and color temperature, hence mimicking the day passing by (though in a fragmented way). Sometime this can be useful, as it was in this project. So far we have used photosequencing in another project where make-believe is a primary goal and its application appropriate and justified. We may not apply it anywhere else in the future, though: when its presence is clearly justified — as we believe was the case of “Deconstructing the American South-West” — the benefits largely outweigh its extremely strong visual signature; the latter in fact — if not carefully managed — can initially attract the viewer with its chromatic abundance yet also hide shapes and forms too much.

We champion non-visual sensations in our photography as a way to expand the viewer’s experience to include more than what is visible on the surface, and to suggest other intangible, non-visual elements that inhabited the scene being captured. In “Deconstructing the American South-West” the searing heat, the fuzziness, the breeze, the flickering before one’s eyes, the subtle feeling of unbalance, and ultimately the possibility to feel either happily lost or happily immersed in this immensity of space were integral part of being there. Thus, we felt that our project was now complete.

- Steve Reich, Writings on Music 1965-2000, Edited by Paul Hiller, Oxford University Press, 2002, p.186-187. [↩]

i absolutely LOVE this work!!! Please say you have a website with much more of this? Please say you’ll do some book covers for me??

ok… gushing over

love your stuff

b

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.