Text and photos by Alex ten Napel.

It was my intention to show another reality of people with Alzheimer’s disease in my series about dementia. The man on the street was convinced that people with dementia did not have a dignified life. The public opinion regarding dementia at that time was that dirty old men and women, being lonely and abandoned, waste away in nursing homes. Pictures shows people with baby bibs on, slobber from the mouth and the remains of a dinner on their clothes. That’s no life! was the prevailing public thought.

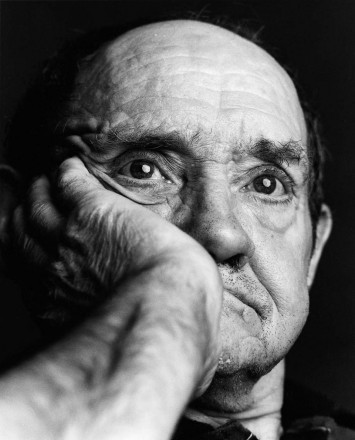

In my photo-documentary I asked myself, what is left of human existence after the destruction of the self by Alzheimer’s disease. While photographing I scanned the faces on signs of an inner life and in my portraits I tried to give an illuminating view on this.

Alzheimer’s disease shows us human existence without any decoration. You see it heartbreaking bright, fragile and delicate in all its details. And you will see more similarities than differences with our lives than you might think. We all are familiar with sadness, joy, fear, despair, depression and cheerfulness. And people with Alzheimer’s feel it the same way. Unfortunately emotions confuse them and…us.

People with dementia wander around in time. They are nomads in their own history and future. It has no beginning or end. Thrown back on themselves their life is totally out of control.

Dementia can alter a carefully constructed personality into a human wreck. The disintegration of the inner life hits the heart of human existence. Our whole life and heart is devoted to develop our personality. A confrontation with people who suffer from dementia can be frightening because their existence raises questions about our own lives. They show us that life can evolve in a different way and their fate makes us sensitive to that.

During my photo project when things weren’t running smoothly I comfort myself with the patients of the nursing home.

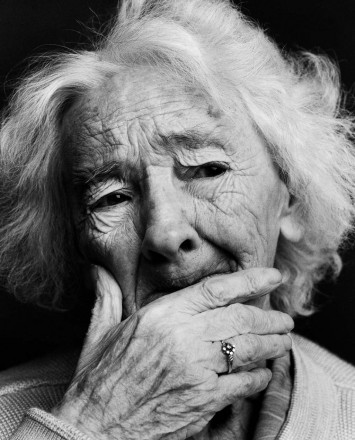

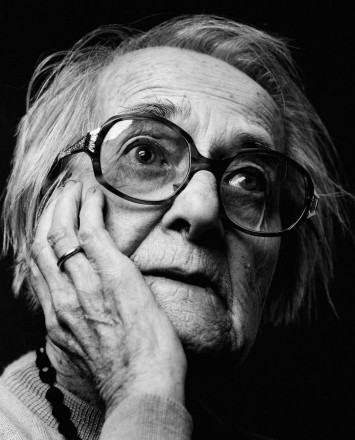

One of my favorites was Ms de Graaff. She was always in a cheerful mood and in a conversation with her my frustrations went up in smoke. These two portraits show her.

The first with her dentures and glasses. The second without. She had lost them. Her face is dramatically changed in the time between. But she had not lost her cheerfulness, liveliness and her characteristic way of handling misfortune and grief. What is deep inside her stays forever. The other dissolves in a life that has been forgotten.

Photography also played an important role in my meetings with people suffering from Alzheimers’ disease. These moments show that in the world I found myself in photography was not what it ought to be.

At the beginning of the shoot, I let the man have a Polaroid photo of himself. He stares at his own portrait. Then he looks up and asks me annoyed:

“Who is this man?”

“What do I have to do with that man?”

Before I come up with an answer he throws the picture on the floor. He looks at me and asks: “Do you have a smoke?”. I give him a cigarette. He smokes it and we start the shoot.

I usually needed more than one hour for the shooting to complete. I had a seperate room in the nursing home which I could use as a studio in order to work in peace. The residents were sitting in front of me in an armchair, a chair at a table or in their own wheelchair while photographing. In this way I could also wait for that specific moment portrait photographers wait for. The special moment in time in which posture and facial expression come together in a meaningful portrait. That often meant a very long wait. My directions proved to be useless and pointless. They didn’t get through to them, they lived behind a wall of misunderstanding. With the camera ready I waited for the moment. Then there is a woman. She is sitting before me with hunched shoulders deep in her own world. She is little. On her lap, she holds a purse. She firmly holds the handles in her hands. Suddenly she comes upright and opens her handbag. A hand moves into her bag. A package emerges wrapped in blotting paper. Very cautious and careful she opens the package. As if it is precious and fragile. A photo emerges out of the paper and she shows it to me. It is a picture from the early years of the 20th century. It shows a middle-aged woman in brown colors of an ancient photo process. She is young and in the prime of her life. On her face are cracks in the surface of the photo.

“That’s my mother,” she says.

“Isn’t she beautiful?”

After a short while of showing the portrait she carefully wraps the picture with the paper and locks it in her bag. Her hands take the handles tightly and her body gets into the familiar posture. The shooting begins, the flash illuminates her proud and happy face.

Much of my time in the nursing home I spent on looking for suitable candidates. I sat at a table in the living room, drank a cup of coffee and had a chat with them. Meanwhile, I studied the people and searched for characteristic postures and facial expressions. In my studio I had some tables and chairs. So they could sit in the same way as they were used to. And I would get the same postures in the studio as I had seen in the living room.

One day I saw a woman holding a frame in her hands. When I sit beside her I see a picture of a baby in the frame.

“Is that your grand child?”, I ask her.

She smiles. Pride appears on her face. When I look better I see under the picture – for children from 9 months -. I understand that the portrait is an advertisement image for baby nutrition. But what makes the image so special that it is in a frame? And why does she hold it so proud in her hands?

“Has your grand child been a model for an advertisement for baby food?”, I ask her.

She looks at me. Not understanding and in confusion.

A nurse who is busy with the dishes intervenes and gesticulates in my direction.

“It has your eyes”, I say to the woman.

She takes the frame and firmly press a kiss on the glass.

Visit Alex ten Napel web site for more portrait photography.

ho amato questo lavoro. nei contenuti e nella forma. Dietro una postura attenta e personale ed una ineccepibile sintassi, mi è congeniale lo sguardo vellutato anche davanti la cruda realtà.

E’ sempre una questione di persone, esseri umani con una loro esistenza e storia, anche se ora è confusa, dimenticata o sfuggita al loro controllo. Solo un profondo rapporto, diretto ed intenso fra il fotografo ed il soggettp può dare risultati di questo livello. Grazie per avere portato alla nostra attenzione questo lavoro.

It’s always a question about people, human being each one with his story even if now forgotten and confused. Only a deep open and intense relationship between the photographer and the subjects can give such high level results. Thanks for letting us know this work.

robert

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.