Photos by Gráinne Quinlan, text by Steven Nestor.

In many ways the roots of Gráinne Quinlan’s White Crane Spread Wings are to be found in her earlier very successful Irish work, Strawboys. In that body of work her subjects were captured and conserved as though Gráinne Quinlan were recording the very last traces of a near extinct group of people for a museum of ethnography. Of course it would be a mistake to conclude that the Strawboys were on the edge of 21st century extinction, but the precise, methodical and still visual treatment is reminiscent of the works of photographers like Milton M. Miller or Imogen Cunningham, which came to be records of disappeared worlds.

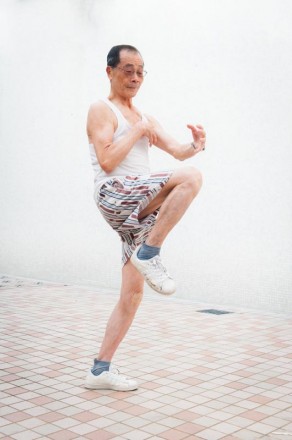

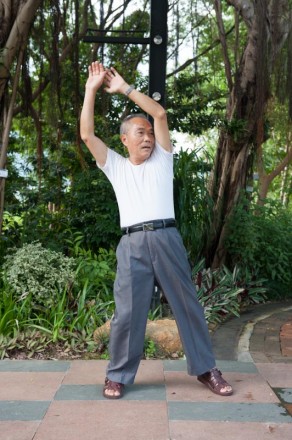

As an extension and evolution of the latter work, in White Crane Spread Wings Tai Chi enthusiasts were chosen for observation, engagement and recording. Most striking in Gráinne Quinlan’s work is that while she is out of the controlled lab-like environment of the studio, the theatricality more closely associated with the indoor space is still very present. While there are few if any “props”, there is a continual sense of the alluring invisible presence of something essential via the stance of the Tai Chi practitioners. I see echoes of Howard Schatz’s work in Caught in the Act (2013). However, unlike the access to famous actors in Schatz’s work, the people of White Crane Spread Wings are anonymous, everyday elderly citizens of Hong Kong. Nor can we consider this work as an attention catching promotional performance. There are no famous faces here to distract and act as crutch to weak or confusing images. Thus, for me words like ‘authentic’ and ‘original’ might be more readily applied to Gráinne Quinlan’s work. I don’t see a reason for the tag of ‘western photographer’ in this work. While the tradition of the Strawboys may be in decline, the enthusiasts of Tai Chi are in the final walk of life, with an art that currently remains strong. Whether the current globalized youth would wish to practice or be associated with the ancient art is another question.

With their shades, visors and grimaces, the subjects are also given individual identities and character rather than being blended into some amorphous “oriental” mass or condescending reverence. Where so often so much of the formal photographic world leans towards profundity and earnestness, a strength in Gráinne Quinlan’s work is her hint at the surreal and humorous. A man seems to have trapped his head in a railing, another appears to have come up against an invisible wall, and a visor-wearing lady looks to be mixing Daft Punk with Beastie Boys. But none of the people look ridiculous or odd in their ritual performance of Tai Chi. Their clothing, hair styles and urban surroundings are, to an extent, imprecise. That is to say, we know that they are in in Hong Kong, but in some frames they might also be in New York or Sydney. There is something of a diaspora to these people. Is it something unique to the citizen’s of Hong Kong or a misreading?

They command their space and, to an extent, the viewer. Indeed, in such a densely populated city as Hong Kong the individual has been drawn out from the masses. These are uncompromised subjects, without the passivism so often found in those studied and photographed, especially by photographers from afar. In Gotthard Schuh’s Insel der Götter (1956) we are invited to marvel — and lust — for the orient ( Java, Sumatra, Bali). It is a brilliant, though classic and oft repeated approach to the ‘other’. Predictably “primitive”, the subjects seem distant, out of reach, unaware of the camera: a puzzling curiosity. I would argue that this – often unavoidable – approach and view is still quite prevalent today no matter how much the photographer or editor attempt to bridge the obvious gap. However, as an outsider (and westerner) Gráinne Quinlan, who has previously allowed herself to be distracted by the “otherness” of HK, has managed to narrow the divide both between herself and the subjects and between the potentially exotic viewer and subject. Perhaps aiding her is the increasingly universal practice of Tai Chi, though that is by no means a free pass to successfully engage with strangers.

Gráinne Quinlan deliberately sought to avoid the group activity nature of Tai Chi and instead concentrate on the individual. As she stated in our correspondence, “group shots tended to lack the visual bite of individual shots”. In fact the group shots she did take have more of an air of cityscape than the practice of Tai Chi. However, changing tack was not a simple decision in terms of execution and her approach to individuals was met with a mixture or flat out rejection and reserved acceptance. The key to making such a convincing work lay in the time spent with her subjects. One can always get lucky once, but the deliberate and consistent nature of Gráinne Quinlan’s work reflects the dedication to her subject and subjects through repeated visits and contact. Describing the practical side of her work to me reminded me of an interview I had heard with Mary Ellen Mark where she talked about how by continually walking the street she managed to become an attractive curiosity herself and was so gradually able to gain acceptance and so create intimate images of the prostitutes of Falkland Road (1981).

As any serious practitioner of photography knows, getting access to strangers, even for the most innocuous subject, can be exceedingly difficult both in terms of overcoming one’s own shyness and getting your potential subject to trust you. “Who are you?” and “what do you want?” are probably the first defensive, self-preserving and reflexive questions asked by those approached in the public space. The public is also far more aware now of the power of photography and potential exploitation and cynicism of the photographer. Clearly Gráinne Quinlan’s dedication and honesty has paid off. The seemingly effortlessness of the images belies the great effort that was needed to successfully execute this work. What we as consumers of her work are left with is a series of photographer-free portraits of interesting people who don’t stare out at us blankly and enigmatically. That would have been cheap and formulaic. Looking at these images and reflecting on the individuals can lead you to quietly conclude that you just might expect to informally meet these people some day and say “I saw you …”

For more photos and stories, please visit Gráinne Quinlan and Steven Nestor websites.

Great work

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.