Text and photos by Loretta Ayeroff.

I was invited to write about my work, over a year ago. I was asked on July 13, 2012, 3:44 AM, for a thousand words. I froze up. Asking me to write about my work seemed overwhelming, let alone, intimidating. I couldn’t do it. A few attempts led nowhere. Probably 150 words, then nothing. Yes, I’ve done artist’s statements, technical articles, syllabi and course descriptions, but this essay seemed impossible. I wasn’t stymied so much about the length, as by the content. What could words reveal that my photographs didn’t? A few months ago, reading the chapter on “Writing” from Why People Photograph by Robert Adams, I felt exonerated:

“The frequency with which photographers are called upon to talk about their pictures is possibly related to the apparent straightforwardness of their work. Photographers look like they must record what confronts them – as is. Shouldn’t they be expected to compensate for this woodenness by telling us what escaped outside the frame and by explaining why they chose their subject? The assumption is wrong, of course, but an audience that knows better is small, certainly smaller than for painting. Photographers envy painters because they are usually allowed to get by with gnomic utterances or even silence, something permitted them perhaps because they seem to address their audience more subjectively, leaving it more certain about what the artist intended.”

Nonetheless, here I am, giving it another try. I’d like to use this opportunity, to answer a question I’m frequently asked: “What do you like to photograph?” Lately, I seem to be conflicted on this point, even posing the question to my own psyche, what DO I like to photograph? How can I answer “everything.” How do I describe what LIGHT means to me, falling on faces, buildings, land and urbanscapes, or, just in its own state of being? Complicating this desire to document light, is my love of photographing without light, seeing how close I can get to the edge of darkness. As I mature, this exercise becomes even more urgent, passing through my lens, what I see in my heart. Perhaps, it is also my changing eyesight, my points of focus seem insignificant. So, this essay, is an attempt to record, in a thousand words, my evolution from “subjects” to “moments” in my photography. Currently, that’s how I answer the question, “I like to shoot moments.”

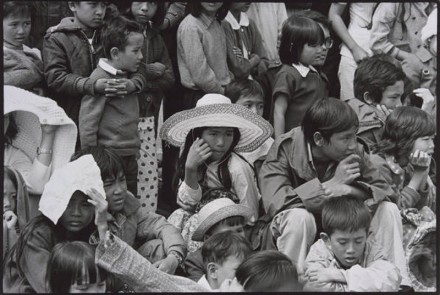

A long time ago, when I was an editorial photographer, I would mostly be assigned to photograph people. I shot portraits, street-work, and journalistic coverage, like my personal project, the “Vietnamese Refugees at Camp Pendleton” now part of the permanent collection “’Nam and the Sixties” at St. Lawrence University:

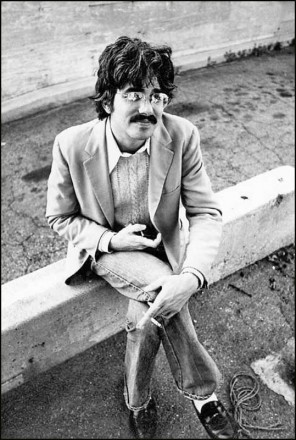

In 1978, Petersen’s Photographic Magazine published a large portfolio of my photographs of men. The Men Series was also exhibited in two exhibitions, with this review, by William Wilson, Art Critic, the Los Angeles Times:

“Loretta Ayeroff stands out from a trio of photographers because she seems to like men without harboring any illusions about them. It’s hard to like any aspect of life without illusions. It’s even harder to feel that way about one’s opposite gender. And then there is the sticky business of getting your feelings on film. Miss Ayeroff’s pictures of men seem to pull this off by simply allowing her subjects to be themselves in front of the camera. (Have you ever tried to be yourself in front of a camera?) One’s admiration goes up and up. Anyway, here are all these chaps being stupid, macho, tender, defensive-dignified, thoughtful, gay or antic like the nude fellow with a potted plant between his legs. Extremely likable pictures.”

The “Men Series” is a collection of portraits, both self-assigned and taken for magazines that I worked for, shot in black & white Tri-x film, with a Pentax Spotmatic Camera. Earlier this year, I was asked to shoot, in the “Men Series” style, for a portrait commission, to be published next month. I pulled out the Spotmatic, replaced the battery, used my favorite 28mm lens, Tri-x film, to much success. I do miss the whole experience of working with the lab, even the waiting period, to see what came out, while the film is being developed. I stopped processing my negatives, decades ago, and my last darkroom was in the late 1980’s. I just gave away my darkroom equipment last year – I wish I hadn’t. There are over 150 portraits, maybe more, in The Men Series. They are regularly requested: a book-cover, and a CD insert, were published last year. I thought I was finished shooting this subject. Recently, however, I realized that I had still been photographing men, in color, using film and digitally, for several years. Surprisingly, I am now accumulating “Men Series II” images:

Still, let me be frank. I stopped shooting portraits, after a reflective moment, twenty years ago, when I told myself that as an “older” lady photographer, I might not be assigned to shoot portraits.

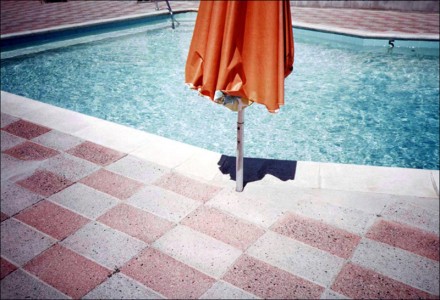

I decided to become proficient at some other subjects. That’s when the concentration on buildings, urban and landscapes began in earnest. “California Ruins” were published in California Magazine, 1982, and one image will appear this year, in an upcoming book by Geoff Nicholson, Walking in Ruins. “The Motel Series,” shot on Kodachrome 64 film, was first exhibited and published, 1987. Last year, four images, from these two series, were included in “Backyard Oasis: The Swimming Pool in Southern California Photography, 1945-1982,” the Palm Springs Art Museum’s response to The Getty Trust’s initiative “Pacific Standard Time: Art in Los Angeles, 1945-1980.” In the exhibition catalogue, Daniell Cornell, Curator, Palm Springs Art Museum, includes my work with artists I greatly admire, Lewis Baltz and Joe Deal:

“Suburbia: “As the dream of a placid lifestyle unravels in the 1970’s, social photographers such as Loretta Ayeroff, Lewis Baltz and Joe Deal began presenting more ironic images. Their frequently wry depictions captured the mundane, sometimes debased, quality of life in suburban developments, for which abandoned or derelict backyards and pools became a poignant symbol. In a photograph of a California tract development by Deal, for instance, the house is pushed to the side and the image is dominated by a kidney-shaped grass yard surrounded by concrete, which mimics the iconic backyard swimming pool even though it is probably beyond the family’s economic reach. Ayeroff and Baltz create strongly formal images that reference human absence.”

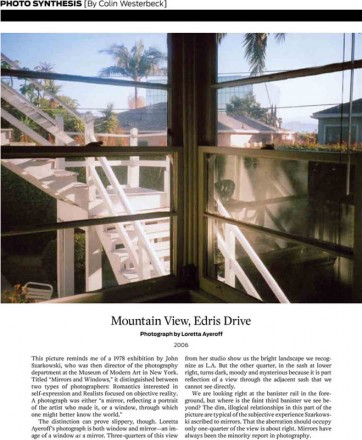

Expanding further, I concentrated on the subject of Los Angeles, my hometown. Although I’ve always photographed my surroundings, with several moves since 2006, a pattern began to emerge. Each new environment, starts with a window, with the light of that window, and what it foretold. There is a “mountain view” from most of the buildings or neighborhoods. This immersion in un-private space, smaller accommodations, un-familiar communities, gave me a seventh sense in adapting to my surroundings. The mandatory interiors, the neighborhood walks, time of dawn and dusk, my checklist for visuals. The documentation began with my studio window on Edris Drive, the last series I shot in film:

“This picture reminds me of a 1978 exhibition by John Szarkowski, who was then director of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Titled “Mirrors and Windows,” it distinguished between two types of photographers: Romantics interested in self-expression and Realists focused on objective reality. A photograph was either “a mirror, reflecting a portrait of the artist who made it, or a window, through which one might better know the world.” The distinction can prove slippery, though. Loretta Ayeroff’s photograph is both window and mirror an image of a window as a mirror. Three-quarters of this view from her studio show us the bright landscape we recognize as L.A. But the other quarter, in the sash at lower right, turns dark, moody and mysterious because it is part reflection of a view through the adjacent sash that we cannot see directly. We are looking right at the banister rail in the foreground, but where is the faint third banister we see beyond? The dim, illogical relationships in this part of the picture are typical of the subjective experience Szarkowski ascribed to mirrors. That the aberration should occupy only one-quarter of the view is about right. Mirrors have always been the minority report in photography.”

Colin Westerbeck, Los Angeles Times

The windows get progressively darker, culminating in “Fifteen Backyards, The Story of a Relationship” shot from one window, over a year, sunrise to sundown:

Citrus Avenue, the first studio of two, around the corner from a former Raymond Chandler residence, contains the red light from our annual, September, fire season. Chandler said, “There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch.”

Reading the novels of Chandler during this period, my work grew progressively darker, with an omnipresent “noir” quality:

Perhaps the studio window from Smithwood Drive, presaged my interest in “moments.” To shoot LIGHT, one has to be quick. There is no time to really check exposures, or carefully frame the scene. The photographs are produced almost like a “grab” shot, quickly before the light changes, or disappears altogether:

So, in my mind, I achieved the goal of expanding my subject matter. My portraiture had become portraits of my life, where I lived, and what surrounded me. Some of the family artifacts that I could no longer keep with me, during this odyssey, I documented. “Body of Evidence” is an ongoing project, becoming the proof that makes the case, my family once existed, despite the deaths and departures:

“Moments” can include all. It’s how I think and see now, no longer restricted by subject, resulting in a panoply of choices… still-lifes, faces, rooms, vistas, corners, branches. An unexplainable mystery, an un-written story, like this, illustrating a Jane Vandenberg column, in the Huffington Post, next week:

I know the result of my shifting perspectives is an un-recognizable style. Whereas my portraits have an Ayeroff “look” I don’t think this is true with my current work. I’m letting the moment, speak for itself, un-encumbered by recognizable framing, or forcing a certain design element. As the photographer, the “mine” fades into the light, only to reveal better, what is in front of me.

For more photos and stories, please visit Loretta Ayeroff online portfolio.

What do you like to photograph? Since a few days, when I first read this article I’m thinking about this question, about what do I like to photograph. Which for me is a terrific question! Your idea not to photograph things or better subjects but moments is interesting. Adds a new dimension, open a different door. I like this idea as an input to find an answer to what do I like to photograph, thanks.

robert

PS: this photo, Window, Smithwood Drive, 2010 is real special, I love it!

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.