Text and photographs by Xiaomei Chen (陈小枚).

For a long time, I liked to look out and travel to distant places, like a dreamer.

“If there were a hell, I know you’d run there just to take a peek,” my mother once said, with great agony. She was right. If hell existed, I’d go to find out what were happening there. I am always curious about places and cultures different than what I am familiar with.

My first trip to Tibet was a turning point that pushed me to look farther out. Instead of traveling to distant places on my annual vacations, I wanted to be on the road all the time. One way to make this a reality was to be a journalist and writer who traveled all over the country – and the world, to tell stories from different cultures.

A year after the two-month trip to Tibet, I quit my teaching job at a junior college in south China to study journalism.

When I first started journalism, I had a lot of romantic dreams. I dreamed I sent articles back to magazines or newspapers from Middle East, Africa, South America…I’d ask unrelenting questions like Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci did.

It was quite nice to study and work for a dream, not knowing, or not willing to know that it would sooner or later be broken like soap bubbles. My first soap bubbles started to break soon after I got my MA in journalism, when I suddenly realized all the skills I had meant almost nothing. I finally admitted I didn’t fit into China’s media system. Besides that, I was told many times that I was like an exile in my own country.

Desperate as I was, I refused to quit dreaming and looking out. I came to the United States to study anthropology, which I believed would indeed take me to all the exotic places – as a scholar this time.

My two years of studying anthropology was eye opening. I learned a completely different way to look at different cultures. Meanwhile, I started to look at my own culture with the theories I was studying. I was trying to verify what I was taught about my own culture. I guess it was at this time that I began to look in, not only into my own culture, but also into myself, though unconsciously. My major interest was still looking out into other peoples.

In 2006, when I was about move to Madison, WI, to study for a Ph.D. degree in anthropology, I took another unexpected turn. I decided to give up my Ph.D. scholarship and became a photographer.

The decision must have been shocking to my family. No one, not even myself, had ever expected me to be a photographer. I could be a writer or professor. Me being a photographer? This was something quite strange. I didn’t even touch a camera, a point-and-shoot camera, until my second year in college!

Yet while an anthropology major at the University of Colorado in Boulder, I audited two photojournalism classes taught by a New York Times photographer Kevin Moloney. Kevin was an inspiring teacher. His enthusiasm for photojournalism was contagious. I soon found myself spending more time on photography than I should have.

Until the end of my master’s program in anthropology, I considered photography an escape from my heavy academic workload. It was fun. That was it.

As it got closer to the day to move to Madison, I grew uneasy. I was not so sure if I really wanted to spend years, maybe the rest of my life, studying one specific culture, digging theories, teaching, debating and researching. That would mean I would spend all my life at school. I had never left school so far. Even before I reached school age, I already lived at school as both my parents worked for a high school and we lived on the campus. After college, I was a teacher… How I wanted to get out of school!

As it became unbearable to think that I would spend my whole life at school – the ivory tower, traveling with a camera and entering other people’s lives seemed so intriguing and inviting. The camera would truly take me to many different places and lives and in a fun way.

As I was debating myself and tried to make a decision, Kevin said to me one day, “The Greeley Tribune (in northern Colorado) needs a photo intern.”

This helped me to make the decision. I gave up my scholarship for the Ph.D. degree and did my first internship with a community newspaper, The Greeley Tribune.

My camera was a passport to enter people’s lives. Every day, I learned something new about America and its people, which I couldn’t have from the classroom. Every day, I went to work with sparkling passion. I looked, and looked and looked… with a camera, and clicked. I was amazed by what I saw and learned.

I kept looking out with my camera and almost forgot to look in until 2009.

2009 was my second year at Ohio University, studying photography with a fellowship. By then, I was a little overwhelmed or confused by what was happening in the world of photojournalism. It seemed all the photojournalistic contests produced similar kinds of work. Winning images were usually dramas of suffering. A lot of my classmates were photographing poverty, homeless people, drug addicts, teenage pregnancy, domestic violence and other negative subjects.

I was not sure if I wanted to do the same thing, though I was sure I still wanted to be a photographer.

Anyhow, I found myself lost again.

I was stumbling and fumbling for my way to do photography.

2009 happened to be a very difficult year in my personal life, too. I was looking for my lost self. I spent a lot of time reading and thinking again. I asked about the meaning of photography, the meaning of, the relationship of life and death.

I didn’t have the answers to the big questions I asked myself, and I still don’t. But something started happening in me. I looked in more than I looked out. Photography might be more a medium to explore my inner world than to look out.

One day I noticed an incomplete skeleton dangling from my neighbor’s window. For the next few days, I found myself staring at the skeleton quite a lot. Then one evening, I borrowed it from my neighbor. I held the skeleton in my arms and walked home in the dark. It was quite bizarre, and a little scary, but I was excited.

I spent a whole week photographing the skeleton in my apartment. I didn’t have a very specific idea of what that would become. I simply followed my intuition and photographed it with an almost playful attitude. Not until I edited the images, did I realize it was a medium for me to explore the relationship between life and death. I had questioned why I existed. The question got louder, but the answer was nowhere to find. This project, titled “Between,” was not an answer, but part of the question.

Puzhu in Transition is another example photography is a medium for me to look in instead of looking out, although it is a documentary project and could be considered a historical record of the Hakka village and its people.

Puzhu in Transition is a multimedia project that includes a book and a video. It didn’t occur to me that I should photograph Puzhu, my mother’s home village, until I visited it again twenty years after my visit as a child.

I was struck by the beauty of this mountain village as if it were the first time I visited it. I was shocked by its population loss as a result of China’s industrialization and urbanization.

A few villagers recognized me. “Aren’t you that little girl who burnt your foot one summer?” They asked.

Yes, I was that little girl, and the daughter of a woman who was born and grew up there.

They were amazed that naughty little girl was now back to their village after a hiatus of twenty years. They were more curious how this little girl, later in her womanhood, could fly over the ocean to the other side of the Earth, where lives were beyond their imagination.

Because I was that little girl, they accepted me and my camera. But because I was not born there, I was not considered one of them. Yet my experiences in a foreign land made them break their rules for me so that I could witness their shrine ritual, which usually didn’t allow women to participate in.

The villagers all know my mother and her dramas when she was young. She was the first person to move to the city from Puzhu. Sometimes I wondered: Had my mother not moved away and then married my father, what would I have become? I sometimes imagined myself growing up in this beautiful but isolated mountain village. I asked many times how my fate as a village woman would be.

All my imagination was vague.

But no doubt the village is part of my identity because my mother comes from there. It is the root of my mother’s and part of mine. Documenting the changes of this village is partly exploring all the possibilities of fate and destiny, which my mother, and of course I, have escaped.

Sometimes I had to “flee” the village when several women preached to me the old Hakka values and urged me to get married and become a mother like any “normal’ woman should. Looking back, I see this as an example of my relationship to this village.

By then, the villagers had accepted me not as a guest or relative, but as a half-member of their community. However far I had traveled and however educated I was, I was still a Hakka woman and was expected to embrace our Hakka traditions and values. They considered it their responsibility to remind me of them. My escape, on the other hand, seemed to reveal my life in limbo partly as a result of being detached from the traditions.

I didn’t grasp the essence of my relationship to the village until after I started the project. Once I became aware of it, my interest to continue the documentation grew stronger. Originally inspired by anthropologist William Hinton’s ethnography about a village in north China over a span of three decades to show China’s history, I am now more certain that the documentation of Puzhu will be part of my life long journey to look into my own culture.

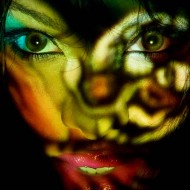

That said, I know a growing interest in looking in will not stop me from looking out. I recently started exploring a subject called “Apple,” trying to push my vision to go beyond limits. Though this subject has nothing obvious to do my personal history, I feel that I am looking out and looking in at the same time. Why? I can’t really explain in words. All I know is photography is my way of looking in and looking out, partly because I seem to be always in an awkward position between in and out.

Very nice picture!!

smoke and light in everyday situation

i love it

moore of this Xiaomei Chen

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.