Text and photographs by Sarah Moore.

How can I talk about loneliness? After all, there are thousands of different types of loneliness. There are thousands more ways to experience it, describe it, or deal with it. Loneliness and its synonyms are so vague, so personal, and so elusive that it seems nearly impossible to address them.

So how do I talk about my experience with loneliness? This has been a question for me perhaps all my life. In fact, loneliness was so integrated in my life for so long that I didn’t even notice it. Yet, after moving from my home state of South Dakota to Rhode Island, where I attended school, this loneliness suddenly felt different. It felt more pronounced, more painful. How could I talk about this new loneliness through my art? How could I even begin to think about it, let alone picture it and share it?

I have written this as a statement of my work titled expanse:

“Throughout the years, I have become increasingly interested in my home of South Dakota and how the people and place shaped me and continue to influence me.

Even though I appreciate many aspects of the Midwest, it represents the pinnacle of the loneliness in my life. When I return, I inevitably regress to feelings of isolation, something I tried to escape my entire life.

My photography depicts the aspects of South Dakota that represent this loneliness for me. The landscape is beautiful but empty, simple but overwhelming. My relationships are based on love, but also thwarted by distance.

Expanses can be comforting but also stifling. Distance can fuel love but also misunderstanding. The vast space of the Midwestern land is something I can’t quite embrace, break free from, or understand, but it provides infinite inspiration for me.”

This statement makes so much sense to me, but I also barely understand it at all. Why does South Dakota provide such inspiration for me? This is the place that saddened me most, that I couldn’t wait to escape from, and that I dread returning to. Yet, with this sadness and dread comes inevitable longing and inspiration. I’ve relentlessly tried to figure this paradox out.

I’ve realized that if anything can describe the ungraspable emotions I feel towards my home, my past, and my family, it’s the land of South Dakota. This land not only provides inspiration for me, but it provides answers and explanations. Perhaps more than anything else I do or say, my photographs from home provide insight into my feelings, and perhaps into those of many others.

Anterior Future photograph. For a long time, I thought I could communicate emotional truths through documentary approaches. My focus was around the house. I believed the distance and loneliness I felt could be blamed on and represented by mundane interactions with my family. The truth was there was an intolerable disconnect between my family and myself when I was home, but the “truth” that my documentary photographs showed wasn’t this disconnect. A lot was going wrong when I decided to photograph at home. My ideas were clouded by strong emotions, and I didn’t have any sort of real focus. I tried to document, I tried to set up, I tried to abstract; I tried everything. Very little was working.“Tell them there was a cow. It was in the field, near where you held the fence. Tell them the cow stood there all day, chewing at something it had swallowed long ago, and looking at you. Tell them how the cow’s face had no expression on it. How it stood there all day, looking at you with a big face that had no expression.”

David Foster Wallace

After a lot of floundering, thinking, writing, and questioning, I had a photographic breakthrough of sorts in October of 2008. I went home for about five days, prepared to make enough images to get me through until I could return in December. I knew documenting wasn’t working, and I knew that my landscapes were becoming more metaphoric to my feelings of loneliness. Armed with these preconceptions, I photographed at home much differently.

Some of my most successful photographs came from this trip to South Dakota. A lot of them were too intuitive to be completely purposeful. I continued taking self-portraits and some documents, but I spent most of my time out in the landscape. I photographed myself in the land and my mom in the land. I finally started to use the expanse of South Dakota’s terrain to represent the stifling emotions I felt at home.

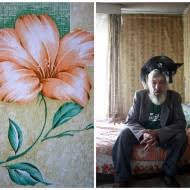

There are a few crucial elements and ideas to my project expanse. Most I realized after the photographs came together; some I realized before I even started photographing. Self-portraiture, the landscape, diptychs and triptychs, repetition, and a certain color pallet are all important aspects of my work.

I now realize that self-portraiture has been important to me for a long time. I have made dozens of self-portraits in the past year and a half. Photographing myself is at once easy, as I’m a model I always have access to, but it’s also much more complex. I thought for a long time that the distance and loneliness found in South Dakota was simple. People grow apart and relationships become strained and what was once close becomes distant.

The distance between my family members and myself is different. It’s a result of physical distance, but it’s also a result of built-up emotional restraint. It’s a result of divorce, secrecy, betrayal, lies, anger, pain, and sadness. It’s a result of a complex home life floating in an overwhelmingly empty and stifling landscape. If I can photograph myself in this land, with some of these people, then I can start to show the other layers.

The self-portraiture in my work is a way for me to show some of these layers in a direct, confrontational, and controlled way. There are seven self-portraits in this series so far. The first and the last were taken about nine months apart. There are four images of me alone, two of my mom and myself, and one of my older sister and myself. These portraits allow me to show the loneliness I personally feel, and they also allow me to show the distance between my family and myself. Seeing the same person in multiple images portrays loneliness over distance and over time.

From the beginning, the landscape has been crucial to my work. At first, I simply took landscapes because I found joy in them. The Midwestern land is something I will probably never grow tired of photographing. The complete flatness of the land is so beautiful, and also so complex. Wherever you turn, you run into what appears to be the same view: expanses of fields, lone roads, and huge skies. With such sameness, the subtleties become incredibly important. Much like photographing the same person over and over again, photographing the land of South Dakota is a lesson in observation and acknowledgement of small changes.

The landscapes also represent the ultimate metaphor for the emotional content of my work. Photographing the land provided a respite from a complex home life. At the same time, the landscape of the Midwest can be incredibly depressing and lonely, which is exactly what it was for the first eighteen years of my life. The land on its own can be whatever the viewer wants it to be–daunting, relaxing, depressing, hopeful, boring, inspirational. When there are people in the land, it can exaggerate distance, discomfort, loneliness, awkwardness, and emotional claustrophobia. Expanses can indeed be stifling.

My use of diptychs and triptychs came from a need to heighten the overwhelming land of South Dakota. A single image couldn’t show the ubiquitous flatness, so I started creating panoramas that emphasized this. Horizon lines are an important visual and conceptual aspect to my work, and expanding these lines allowed viewers to better understand my ideas.

The multi-paneled images have become much than just an aesthetic choice. Piecing together two or three photographs allowed me to break up both people and land. I could guide my viewer through an image by using focus and lines in diptychs and triptychs. I could put my mom in the middle of a three-panel photograph to emphasize her aloneness next to the vastness of the land. I could break apart my own head in a diptych to at once push myself to the edges of a single frame and also join them to create a seemingly whole portrait. I could put different figures in different panels to exaggerate physical distance. And, of course, I could break up my horizon lines to address the confusion of this landscape and debunk the idea that it is easy to understand.

I used repetition a lot in this project. It’s hard not to repeat a landscape that is actually so similar everywhere you turn, and it’s hard not to repeat when self-portraiture was used so often. Facial expressions, poses, lighting, seasons, and sequencing kept this repetition from becoming boring. The same people and same landscape kept this repetition working conceptually. My loneliness in South Dakota didn’t just occur once or twice, but every time I went home. It also doesn’t just occur when I go home, but other is instead an integrated part of my personality, for better or worse. I wanted to portray the Midwest as I felt it, and I as I continue to feel some other places. Sometimes hitting the same note over and over again can be a wondrous form of poetry.

The color pallet of my project is composed of many browns, beiges, and grays. I used the occasional bright color, in a scarf or road perhaps, to break up the monotonous color scheme. Subtle colors shifts in the land and sky were the most captivating to me: when the light changed just barely from blue to gray to red, and when the ground swayed from dark to light brown within one plain. As long as I could control my lighting and color choices, I could better dictate how the photographs would be read.

“When do you know when something is becoming something that changes you?”

Daniel Handler

Throughout the course of this project, I have learned a lot about my personal loneliness and distance. I haven’t answered a lot of questions, but I’ve been capable of at least asking them. The vague concept of loneliness, the universal idea of home, and the personal ideals of land have come closer to being within my grasp.

I still don’t know what these photographs say to or about my family. The project evolved from a personal place to an even more personal one. I know what I see when I look at these photographs, and I know what a select few friends, teachers, and peers see, but I’m not sure what the universal statement is. Yet, I’ve always liked my work to be slightly ambiguous, slightly hard to hold onto. I tend to not like the obvious; I’m not an obvious person. All along, I’ve just hoped that if I produce images that really mean something to me, then perhaps they’ll mean something to others.

I said before that I could photograph the Midwestern landscape forever. I know this is true, but I’m also not sure if it will always have something important to say to me. This project hasn’t come to an end yet; if anything, I’ve just begun. I don’t know how long I’ll continue using my family and my homeland to talk about my personal ideas. I’ve learned that I can address things best through the land, but this doesn’t have to be a particular space. Expanses will always be important to me, but I know I can find them everywhere and through almost everyone. I hope to continue to tie emotions to the outer world, whatever and wherever they may be.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.