Text and photographs by Jens Olof Lasthein.

I was born three years after the Berlin Wall was built. My childhood was marked by the division of Europe, the sharp line between East and West. External political conflict shaped inner mental boundaries that had to be confronted – who are they; who are we?

I travelled through Eastern Europe for the first time in the summer of 1984. At the age of 20, I had long wanted to see what life was like on the other side of the Iron Curtain, the part of Europe I could only fantasise about growing up in the West. I didn’t doubt that the media image of a uniformly grey, comfortless world wasn’t the whole story, but I had little idea what to expect instead.

I travelled the way I always did in those days: by hitch hiking. Highways were practically non-existent, so drivers had no trouble stopping to pick me up and I made my way at a slow but steady pace. Afterwards, I still wasn’t sure if I knew the answer to my question about what it was like on the other side, but at least I had met many Eastern Europeans.

There was Dora, quiet but somehow intense, whom I met in a Budapest restaurant when she left her telephone number on a napkin. Later I would live with her in Kazincbarcika, and I can still see her before me as we waved farewell outside the petrochemical factory where she worked.

There was the frightened silence in Sibiu when someone whispered “Securitate!” And the German woman, Gerda, who didn’t waste time worrying about the secret police but invited me in for dinner, serving smoked blubber in her dirt-floored kitchen. There was Kapika and his friends from Zaïre who lived in a student dormitory in Cluj, laughing uproariously at everything while preparing a feast from bits of meat, some onions and a few tomatoes. Handsome Kapika, who had a child with one Romanian woman and was having an affair with another.

There were the two East German girls I met out on the puszta, Hungary’s semi-desert steppe, where we spent a night camping out under the stars. Awakened by lightning, we set out walking through a dark and rainy night toward huge gas flames shooting into the sky – a factory out in the middle of nowhere. The guard couldn’t believe his eyes when we showed up at the gate, but he was kind enough to let us in to get dry.

There was the old man, so fat it was a wonder I could get both myself and my backpack into his Trabant, which had to stop every other kilometre to let the spark plugs dry.

There was Bogdan from Krakow, who picked me up in Czechoslovakia. He was one of the few people who consented to speak Russian, the only language we had in common. Most people refused, even though everyone learned it in school. He invited me to visit him in Poland, where he took me on a tour of the enormous Nowa Huta steelworks. A year later, Bogdan’s wife Halina wrote me a letter to say that he had died in an accident with the same Polski Fiat in which I had hitched a ride, leaving her alone with two small children.

There was the party in Katarina’s tiny apartment, where we squeezed together in her bed and sofa, enveloped in thick cigarette smoke, with Paweł Orkisz, always the life of the party, playing his guitar and alternating between his own songs and interpretations of Okudzhava and Vysotsky.

There was the Gypsy shepherd, who woke me early one morning as I slept under a tree, and had me watch the village cows while he ran off to buy a bottle of palinka brandy with my money.

There was Andrzej, whom I met at a café in Warsaw and who perhaps regretted inviting me home because his boyfriend Ryszard, a film photographer who always bought the drinks when we went out to bars, took a liking to me and spent most of the night trying to seduce me.

And there was the charcoal burner Karoly, who had fled from society to live in the Bükk nature preserve, where I was regaled with warnings of the coming downfall of civilisation under the crushing weight of individualism and consumerism.

The Berlin Wall fell in 1989. I remember the depressing sight of a Marlboro delivery lorry backing into Potsdamer Platz to bestow the long-deprived East Berliners with specially produced mini-packs of cigarettes. On the flip-top was printed: “Marlboro, the taste of freedom and adventure.”

A couple of years later the Soviet Union ceased to exist, and when I travelled to St. Petersburg in 1993, Russian society was just climbing out of the rubble of a collapsed system.

The years since then have seen new boundaries rise up between Europe’s east and west, and this is the borderland I have visited most recently, from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south. Isolated moments and fragments from these travels make up the images and tales in my book, White Sea Black Sea.

St. Petersburg – Tallinn, 1993

The train slows, finally coming to a stop. Outside is – nothing. I look questioningly at the jovial conductor with whom I am drinking tea and vodka in his tiny compartment.

“Hurry”, he says, pointing to a small station building with a light shining in one window.

We’ve come to the new border between Russia and Estonia.

Suddenly the tracks are overrun by people trying to be first into the little structure. Chaos breaks out, with yelling, swearing and jostling. Industrious men try to push through the crowd with bundles of passports. It’s impossible to know which window to go to, but it’s obvious the right decision has to be made quickly. Even though I’ve abandoned all courtesy and joined in the shoving, I’m pushed further and further towards the back.

Now the ticket checker is beside me, gesturing for my passport. He disappears, and a sense of unease falls over me. Then I see him, over by the entrance, with a distressed look on his face. He furiously waves me over, pressing my passport into my hand and running ahead of me to the train. We’re barely aboard before the whistle blows and the train begins to chug away. Everyone who has failed to get the required stamp is left behind, watching us disappear into the night.

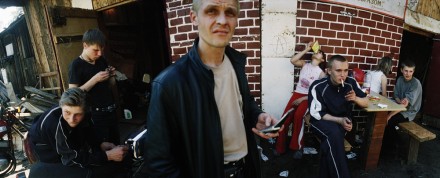

Arkhangelsk, 2005

“Come on! We’ll do it like we did in school!”

The two festively dressed gents on the quay look surprised as a half-naked man who has just climbed out of a motorboat dances around them with clenched fists. They try to ignore him, but it’s no use. He won’t give up. Finally, one has had enough and beats him to the ground with several quick blows and a well-aimed kick to the head.

Five minutes later the underwear-clad man is back, going after the other partygoer with renewed energy. But this guy is no worse than his buddy. A crunch, and then a thump as the back of the drunk’s head hits the asphalt.

Arkhangelsk. The very name rings of permafrost, darkness, endless forests and icy wastelands. But now it’s a new town. I walk for days on end, and when my legs won’t carry me any longer, sometime after midnight, I futilely attempt to close out the sunlight with a bedspread over the window. By 7 o’clock I give up and pull on my shoes again.

There’s electricity in the air. The throngs of people crowding the beachfront walkway never seem to want to go home, choosing instead to take a stroll over to the unknown soldier’s eternal flame, or the go-cart track wedged between the pier and the disco boats. The annoying whine of two-stroke motors doesn’t stop until well past midnight. The scent of sjasjlik – grilled meat on a stick – hangs heavy in the warm evening air. The midnight sun perches stubbornly on the distant horizon, refusing to drop below the arms of the river delta.

Kaliningrad, 2007

The girls look about the same age as my daughter, maybe 11 or so. Like young girls everywhere, they try to look older with make-up and high heels, short skirts and silver belts. A torrential rain is falling, and the ancient drainage system – a holdover from the time when this seaport was known as Königsberg – doesn’t have a chance of carrying away all the water. We stand in a doorway to keep out of the downpour, but when the girls see puddles grow into lakes they can’t hold back any longer. They run out into the street, laughing and shrieking.

Shoes come off, and on, and off again – the girls can’t get enough of this. Now they’ve discovered that the road at the bottom of the hill has turned into a river that cars can barely get through. There, soaked to the skin, they completely forget the limitations that make-up and heels place on older girls.

Sofiyovka, 2005

The air stands still between the houses, and the puddles are evaporating under a strong sun. The only sound is a distant hammering and the clucking of a few hens and geese behind a fence. A bread truck breaks the near-silence, pulling in on the patch of dirt to deliver crates of newly baked loaves to a shop in what I thought was a ghost town.

Laughter and loud voices. An engine starts and a dented old car tears away in a cloud of dust. Outside the youth centre, Aleksandr wonders if I’d like to come inside. Light falls in through ragged lace curtains in chilly rooms that might have once served as a pioneers’ meeting hall. A wood stove, a few chairs and a disassembled motorcycle are the only furnishings apart from a three-legged pool table with one corner propped up by a chair.

Aleksandr selects a cue, and with a crushing break shot sinks one ball. He moves to the other side of the table; I step around in the opposite direction. We have stopped speaking, and a curious tension builds with our slow movements around the table. Aleksandr ponders his next shot, sights along the length of the felt surface, changes his mind, goes back, aims carefully and shoots. He seldom misses.

Straightening his back, Aleksandr circles the table looking for a shot. He’s also moved into the right place for my shot – with a camera. “Stop,” I say. He looks up, and my lens pans slowly over the scene. When the motor stops humming, he cracks another ball into a corner pocket. Now whenever I like what I see through the viewfinder I just say “stop” and our eyes meet over the table for a long exposure, and then the game continues. I don’t know how long this goes on, but when I step outside into the hard sunlight it feels like I’ve been holding my breath for a very long time.

Stolnitsy, 2004

Alisa looks through the gate towards the high barbed-wire fence cutting across the main street a few dozen metres from her house. Has the neighbour on the other side come home yet?

Stolnitsy was once an ordinary Hungarian-speaking village under the dual monarchy. Then came World War I, and Stolnitsy became part of eastern Czechoslovakia. Nothing strange about that; borders in this corner of Europe have been moved fairly often during the course of history. But things got more complicated by the time World War II was over. The village was still Hungarian, but the Yalta Agreement gave the easternmost part of Czechoslovakia to the Soviet Union. Stolnitsy was split down the middle, right over the main street, with barbed wire, mine fields and a guard tower.

And that’s how it remains when I come to visit Alisa. The mine fields are gone and the old guard tower stands empty, but the cruel wire fence is still there, patrolled now by Ukrainian border guards on this side and Slovakian EU soldiers on the other. So when Alisa wants to have a cup of coffee with her nearest neighbour, they stand on either side, giving the wire a respectful distance, shouting and gesticulating, both of them speaking Hungarian.

Chernyakhovsk, 2007

The boys are taking turns on their shared bicycle, sprinting around the block and spraying gravel when they brake. I commend the exquisite spoke decorations – red and orange plastic shooting stars. Now one of the lads is climbing along the gas pipes running over our heads. It’s obvious he’s done this may times before, but I can’t help feeling a bit anxious as I watch him balance up on those narrow tubes.

The boys appear to be on their way someplace else, but they can’t seem to pull themselves away. I shout good-bye and begin walking away. One of them comes running after me.

“Have you got a bicycle at home?” He lights up when I say yes, sure I do. He kneels by his bike, pulling loose two plastic beads and a bright orange shooting star.

“Here you go,” he says proudly, and the two of them disappear between garages and wash lines.

“The Zone”, 2005

Bragin is an unassuming little town in Belarus, close by the border with the radioactive area surrounding Chernobyl. There are five exits from the traffic circle just south of the municipality, one of which features a guard shack and a boom. To the left, oddly, a parallel road runs straight into the Zone.

Climbing out of the car a quarter-hour later, I can’t see the asphalt for the thick covering of leaves. Buildings are only partially visible behind the trees and bushes that have grown up unattended over the last two decades. A rusty sign points the way to what once was a side road. Roofs and walls have collapsed, and through a broken window to what must have once been a medical clinic I see a rusted gynaecology chair. There isn’t a sound.

I stop outside a school. The memorial to the Great Patriotic War of 1941–45 looks lost and helpless. Suddenly, as if the projectionist had switched to the wrong reel in the middle of a film, the silence is broken by singing and laughter. Confused, I stumble out of the bushes and very nearly collide with two quite drunk ladies on bicycles. They laugh heartily when I ask if anyone actually lives around here, and point down the road before re-mounting their bikes. I drive in the direction they indicated.

Behind a high fence a dog is barking, high-pitched and angry. Strangers don’t often pass this way and when the gate opens and the dog comes bounding out, his excitement is so great he’s got an erection. Leonid and Vladimir have lived here all their lives. They don’t know where else to go, so when everyone else evacuated after the nuclear accident, they and a handful of other families simply stayed put. They grow their own potatoes and shrug off stories about radioactive uptake. Ivan comes by leading a horse and wagon loaded with planks. The red sun is low in late afternoon sky, and he’s already well and truly drunk. He slaps the horse’s rump and staggers off along the lonely road.

Back in the semi-darkness that has fallen over Bragin, I find what may have once been a better restaurant. On the menu is pork chops and potatoes. While I eat, the other guests are arguing over a bottle of vodka. One of the men pushes angrily away from the table, falling off his chair. His woman stumbles off in disgust.

Julia is a cancer physician at the local hospital, where I pay a visit to her tiny apartment. She’s gorgeous, and I’m more than happy to sit and chat while we drink Champagne – until her mobile phone suddenly rings. A fearful look crosses her face. No time for formalities now – the police have found out that I’m here and she shows me a back way out of town.

I travel a good distance northwards before stopping. In the darkness, under an impressively starry sky, the tension lets go.

Kegostrov, 2005

Stepping ashore from the riverboat that morning, I see the rusting hulks of old ships, lying where they’ve been drawn up on land and never put to sea again. I return to the wrecks at the same time two boys come riding up on their bikes. One is a couple of years older than the other, and both are named Alyosha. I feel an expectant, almost reverent tension in the air when I walk up and say hello. I need to be careful; it’s better to say too little than too much. I begin taking pictures, letting the tension build and keeping the boys’ gaze locked in mine.

The younger one is a little reserved and can’t seem to relax, but the older lad seems to possess an instinctive sense of self-worth. He opens up his rucksack to show me the day’s big find: a crow! It looks like one wing is broken, but it’s a living crow, which the elder Alyosha takes in his arms and pets before placing it on his shoulder. It flaps a bit, but stays put.

Using this panorama camera requires a fairly slow pace – each frame has to be wound forward – and we soon fall into a close, almost meditative co-operation. Each time I change film rolls, the older boy alters his pose, moves the bird, and asks with his eyes if this looks good. After a while the younger Alyosha falls into the game as well.

By the time I leave, they’re deeply into their own game: back and forth between the boats, up to the cabin, down in the hold. The crow has no choice but to follow along, occasionally being thrown into the air in well-meant but tortuous attempts to get him to fly.

Later that day I run into the older Alyosha in the garden in front of his house. He’s digging a grave for his bird.

Grigoriopol 2006

Heading north out of Grigoriopol, I happen to look down a small side road towards the river and see a man swimming with a goose under his arm. What a photo! I run, but just before I get there he releases the goose.

It turns out to be an old ferry dock. But the other side of the Dniester is now enemy territory. The barge no longer runs, instead lying rusted on the riverbank. The afternoon sun is warm, and the place has a strange atmosphere. Suddenly a horse-drawn wagon comes careening at high speed down the bank carrying Ivan, Grigorij and Ljuba – father, son and daughter-in-law.

The plan is to wash some rugs and the horse, but first on the agenda is a picnic. As the watermelon is sliced and the vodka glasses are filled, they tell me of their friends and relatives on the other side of the river, in what used to be the same Soviet republic but is now another world – Moldova. They almost never see them any more. But they can live with that; they’d never consider moving from their breakaway republic.

Now it’s time to wash down the horse, and Grigorij rides him bareback, far out into the Dniester’s swirling currents. Next is a swim among the river’s geese, more vodka and cigarettes as afternoon turns to evening and we say farewell.

Much later, with darkness now fallen, I feel a twinge of melancholy as I cross the border at Dubăsari, leaving Transnistria, the last Soviet republic.

The new eastern edge of the European Union is not the sharp, merciless border of the Iron Curtain, but it remains palpable for everyone on both sides. Whether this new demarcation is an absolute one remains to be seen – and it’s up to us to decide how much we will allow it to affect our inner boundaries.

Every time I travel to the east, I re-live my first trip back in 1984. As foreign as the world on the other side may be, there’s always a strong but indefinable sense of coming home.

For more photographs please visit Jens Olof Lasthein website.

Inspiring work! Thanks for sharing.

Terrific images. It’s incredible how much Eastern Europe has changed. You are fortunate to have traveled there in the 1980s.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.