Text and photos by David Parker.

Some years ago I rescued an anonymous 19th century albumen print from a London shop window. Its only protection from the sun was a thin plastic sleeve on which a price tag of £12 had been stuck. Sadly, the print showed that the Sun had started its implacable work by leaving a very faint shadow of the sticker on the already pale sky but I bought it anyway because I liked the image.

In the way that pictures from this time often reveal a mysterious lost world, I found it powerfully alluring. Seductively coloured in those warm sepia-like tones on a paper yellowed with age, typical of prints from this era, the image depicts a harbour scene somewhere in the tropics. Beyond the thick stand of palm trees, single funnelled merchant freighters in the mid-distance are offloading cargo into barges via tubular chutes. A solitary white 4-masted clipper breaks the skyline at a point approximating the Golden Mean of the image. For me the whole scene instantly evokes the humid atmosphere of a novel by Josef Conrad.

The location of this image is a mystery to me. Over the years this has become one of its attractions and I’ve never had a wish to discover its identity. I can therefore enter the scene with my own narratives and sense of wonder intact. In ‘Middlemarch’ George Eliot writes:

“He said he should prefer not to know the sources of the Nile, and that there should be some unknown regions preserved as hunting-grounds for the poetic imagination”

I tell this story by way of indicating my response to the question most often asked of my own pictures, “Where is it?” At first I was uncomfortable about refusing to disclose locations. After all, it’s a natural enough question. But over time I’ve been encouraged by the acceptance people have about this anonymity. Perhaps they think as I do that in a world that has now been saturation-mapped there is still a need to discover fresh vistas and to know there are still places ready to offer us enchantment and glimpses of eternity.

So if you know or suspect the location of the anonymous picture, please, please resist the urge to send me a ‘helpful’ email, I’d rather not have my mind put to rest over its identity!

For me, 19th century photography offers a kind of magic carpet ride into a world of mystery and lost histories. Back then the new medium was very largely a rich man’s hobby but was also seized upon by scientists, geographers and artists. We know very little about the aesthetic intent of many of these individuals; the divisions between document, reportage and expression were not then as clearly defined (and remixed) as they are now, and therefore there is an inherent ambiguity in our interpretation of their images. What is clear however is that in this embryonic medium, dominated by painterly conventions, a few practitioners such as Cameron, Teynard and Greene, often working in isolation, developed recognisably photographic sensibilities; that is, an awareness of the camera’s unique way of seeing the world; the aesthetic of the image claiming primacy over its content.

At this distance in time it is a little hard for us to grasp the impact of the pictures made by Carleton Watkins in Yosemite in the 1860’s. They so entranced people of the time that it was quickly designated a National Park, and ironically also inspiring Albert Bierstadt’s massive paintings that initiated the period of the ‘Western Sublime’, which in turn inspired the mid 20th century American f.64 school headed by Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and others.

More than a century on from the work of these early great photographers, the seminal ‘New Topographics’ exhibition in 1975 reflected our continued concern with depicting the landscape, and carried with it an implicit disavowal of the ‘pictorialism’ and ‘monumentalism’ of the early 20th century photographers. After this exhibition making landscapes in the manner of the ‘Southwest School’ became as relevant as writing symphonies in the late-romantic style. It therefore seemed to me problematic to return to the sylvan landscape without taking on board the work of Robert Adams, Stephen Shore and others, with their very human take on the subject, but I felt that it was a job worth attempting. I was not working in isolation: Mark Klett and Thomas Joshua Cooper were also clearly taking their markers from the early masters, and both had in mind long spans of cultural and geological history. My own agenda was to find a way to re-explore with a modern sensibility the ‘monumental landscape’ of the 19th century by seeing it in terms that were symbolic and metaphoric rather than theatrical and rhetorical, by fashioning an austere beauty and using techniques unavailable to the early pioneers. Moreover, I wanted to occasionally integrate the human element into my pictures in a way which not merely gave a sense of scale but also affirmed our fleeting presence within the landscape, in other words, using the landscape to put ourselves into some sort of perspective by leaving traces of our passing through it.

The remit of contemporary photography, to ‘witness the times’, is one that increasingly I feel rather detached from. Social criticism in the arts, didactic art in other words, is very limited in what it can say about geologic timescales, and I share with many people a need to experience art which can take me beyond the temporal and quotidian. Before going any further I need to renounce any personal claims to aesthetic purity, since my first project Broken Images, about the Nazca Lines in Peru, was concerned with the collision of the temporal and eternal, and was photographed in full colour in a reportage style.

In contrast to this earlier work, key to my landscape projects was a deliberate striving after beauty, and here I need to digress slightly. For many years I have been greatly affected by the power of beauty in art to arrest the mind and attune it to another level of consciousness. Even a secular soul like me is irresistibly enchanted by the nave in a medieval cathedral, the choral harmonies in a Bach oratorio or the deceptively simple abstractions of a Paul Klee painting. Beauty has been described recently by the English sculptor Grayson Perry as ‘the elephant in the room that many artists find difficult to ignore’. Beauty requires no commentary for its appreciation and no validation by a priesthood of academics, though this can sometimes deepen the experience of it for someone already engaged with an artwork. T S Eliot observed that ‘All great art communicates long before it is understood’. And I think that the rhythm of beauty is the vehicle that engages us in what James Joyce calls ‘aesthetic arrest’, that moment of revelation which makes us one with the work.

Beauty has always been contested territory and doubtless will continue to be so. Many artists remain deeply suspicious of beauty and ignore it altogether, and for fear of being misunderstood are eager to have the subtext of their ‘difficult’ work explicated rather than risk it being judged only at face value. Of course beauty is subjective and comes in many forms, for example, an experience of the Sublime is often described as a ‘terrible beauty’. Beauty, as against mere chocolate box prettiness, is capable of carrying deep reservoirs of thought, consolation and redemptive power, and reminds us in a poetical way of our shared myths and history. So, far from beauty being in some way regressive, conservative and irrelevant, it remains alive for me as a ideal to aim for without reservation.

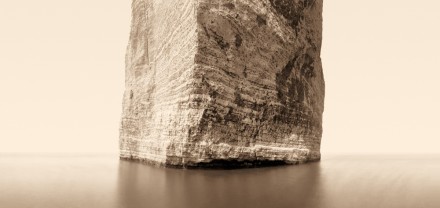

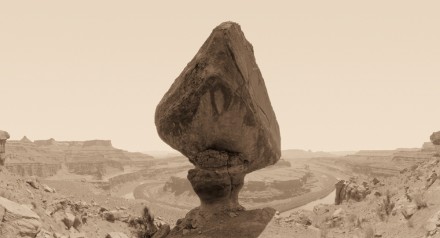

‘The way forward is the way back’ wrote Eliot, and for me at least this meant finding a form to utilise the visual vocabulary of photography’s forefathers, one that was steeped in beauty. Revisiting the 19th century landscape with its aesthetic of narrow but rich tonalities, offered me a potential way to excite feelings of wonder and awe, curious emotions which at once fill us with enchantment and a sense of our mortality. Feeding into my enthusiasm for the work of these pioneers was an interest in myth, legend and classical literature, the human rather than the political face of culture, and from this mix I fancied that I began to see striking features of the landscape in ways that our ancestors might also have seen them, first as beacons and landmarks, then perhaps in anthropomorphic terms and even as ritual totems, all hinting at a relationship to the landscape that was both utilitarian and, dangerous word, spiritual.

Natural arches, for example, become bridges between worlds, thresholds of transition. Solitary sea-stacks become sirens awaiting the unwary seafarer. Caves become entrances into the labyrinth or the abodes of oracles. The Earth’s geology was and is therefore a mythogenic zone which the human psyche is able to embrace in ways that are metaphoric and symbolic. Philosophically, these are of course large subjects and well beyond the scope of a single artform such as photography to convey, my personal aesthetic remit is to still the mind of the spectator into simple fascination of the world.

I knew from the outset that I wanted to use a proper panoramic camera for this work, one that covers a wider angle than human vision, not only because of the way that its deep perspective emphasises foreground subject matter, but to metaphorically expand our view of the world. For a few years I’d been experimenting with several panoramic cameras but was unhappy with the letterbox shape they all produced, which I felt gave undue prominence to the format over the image content. Finally I discovered that the Swiss company Seitz produced a made-to-order 360-degree panoramic camera that used 5” military reconnaissance film. Designed originally for interiors and group pictures, the Seitz produced an image more than twice the height of other cameras. Fewer than 10 of these cameras were ever made, but for the brief period between their production and the shift of the military away from film towards digital, they produced images of a quality that couldn’t be achieved any other way. However, full 360-degree images look almost always ‘tricksy’ because of the inevitable distortions, but I discovered that limiting the range to less than 180-degrees of the natural scene made these distortions almost unnoticeable. And with a vertical angle of 80-degrees I was able to produce images with much more regular proportions: approximately 2:1.

I still had to find a way to produce the large prints I envisaged, 2 metres x 1metre, and since I also wanted to produce prints which had the colour palette of faded 19th century prints this presented further challenges. Colour photographic paper proved to be lacklustre and too narrow in tonal range, and eventually I settled on toning black and white paper. Managing fibre-based paper on this scale sent me literally back to the drawing board to design a machine capable of handling it. I had reached the point of submitting prototype drawings for tender when I was told about a French system designed for colour processing that might just work with b/w paper. It was a further 3 years of work with this system that enabled me finally to make prints that I was happy with.

The characteristic tonality of 19th century photographs invariably produced bright featureless skies and dark foliage. The reason for this is that all early black and white emulsions were only sensitive to blue light. Blue sky would therefore be strongly registered, green much less so and red and yellow almost not at all. Blue sensitive emulsions have not been available for many decades; however I was able to find a blue filter which corresponded to the spectral sensitivity of wet collodion glass plates and this has since been an essential feature of my work. Atmospheric haze, being at the blue end of the spectrum, is greatly amplified with this filter and produces a graduated series of fading planes disappearing off to the horizon, blending softly into the infinity of the sky and enhancing the sense of perspective and limitless space.

Another feature of the 19th century collodion process that impressed me was the fine grain image quality that could be achieved. This was just as well because photographic enlargers didn’t exist at this time, so large images had to be contact printed from large glass plates, necessitating equally large and cumbersome cameras. ‘Mammoth’ plates, measuring 22”x18” (56cm x 46cm) had to be coated on location in a small tent, a delicate and toxic procedure requiring great skill. The plate then had to be loaded into the camera and exposed before the collodion dried, and immediately rushed back to the tent for development. Taking advantage of their blue sensitivity, the plates could be coated and processed in the yellow light provided by a small coloured window in the tent. Setting up a tent could take as long as setting up the camera, so it is understandable that many photographers chose to leave the tent in the picture rather than move it.

A few years after I had managed to make my own prints, I had the good fortune to examine a copy of the 13-plate ‘Mammoth’ panorama that Edweard Muybridge made of San Francisco. Spread out, the view measures around 17 feet long (5.2 metres) and is full of breathtaking detail when viewed close up. It is clear that part of Muybridge’s aesthetic gaol was to immerse the spectator in a high-resolution spectacle. It must have mesmerised all those who first saw it and even a 100 years after its creation it still had the power to raise hairs on the back of my neck! This experience confirmed me in my belief that the delicate rendering of detail could almost be an end in itself: the way that something is photographed is at least as important at what is photographed. If an image has already engaged the viewer, such a wealth of detail has the power to delay the eye still further in fascination.

Composing images with the Seitz requires a different approach to judging the forms within a scene because there are no viewfinders capable of properly rendering such wide angles without distortion. I therefore had to devise simple protractors that would reliably indicate the reach of the camera lens, forcing me to visualise the balance of the composition in my head. Not surprisingly, these methods had their limitations and I often had to return to a site several times before getting the image I was looking for, sometimes repositioning the camera only a few feet. Post manipulation in Photoshop was not an option because the images would ultimately have to be printed traditionally with a negative in an enlarger, and there wasn’t then or now, a way to generate a negative from a digital file with sufficient resolution to substitute for the original. Ultimately, I found that processing on location in my campervan was the best way to ensure compositional accuracy, ironically a nod back to the early pioneers developing glass-plate negatives in their tents, and also using printing-out-paper (POP) on location to finely judge the result. This involves sandwiching the negative between the sensitised POP and glass and exposing to full sunlight for a few minutes. The paper is then fixed and toned for permanence.

It is always an exciting moment to see the first print because up till then, without a viewfinder, the image can only be visualised. With its panoptic reach the camera is revealing an image that the eye simply cannot encompass. The still photograph thus becomes the mediator between the real and the imagined.

An unusual feature of 360-degree cameras is that they scan the scene with a vertical slit whilst rotating and pulling the film across the shutter. With my particular menu of filmspeed, processing and filtration, the time taken to shoot 180-degrees is between 4 and 8 minutes. A serendipitous result of this slow rotation is that people sometimes unwittingly appear twice in the same picture. Limbs might be truncated or shadows liberated from figures. This unanticipated discovery enabled me for example, to place my disembodied hand on a rock surface in an echo of the hand prints left in caves by our earlier ancestors.

About a year ago I switched to archival pigment printing because the process of printing and toning large pictures in the darkroom became unsustainable with the disappearance of suitable papers, environmental considerations forcing the elimination of the heavy metals needed to give these papers their unique depth and lustre. However, I’ve embraced this change with enthusiasm because in my view the gains have significantly outweighed the losses, though for some people traditional vs. digital will always remain a theological battleground. The history of photography is one of constant technical developments being the father of aesthetic innovation, and I’m as excited about the digital revolution as daguerreotypists must have been when wet-plate photography arrived. I am now enjoying the ability to produce prints with a fidelity to my original intentions that were often impossible in the darkroom. Anyone who has ever laboured for hours in a darkroom over a single print will understand this.

If you have stayed the course with me this far, thank you.

Please visit David Parker website for more informations and photographs.

I love David’s photos – they transport me out of the present and into deep time, the vast waters and the empty sands, where the earth can speak to the quiet spirit that cowers beneath the rush and roar of daily life.

wonderful, I’ve also seen many in their exhibitions. What creativity and what a spirit to have the creativity. The essay is fascinating. Thank you David. Looking forward to the next exhibition.

Truly artistic work here from a man who sees life through a different lens. My myopic eye sees beautiful lines to climb and I love the Hand as touch is the essential sensual part of rock climbing and Gaia

this is really cool

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.