Maury Gortemiller sent me a long and excellent article about his work and vision.

On the one hand he explains in detail his thoughts on photography and aesthetics, on the other he describes two of his conceptual photographic series: No Anthem and Speed Queens. Maury Gortemiller explains the reasons that led him to use a snapshot and seemingly casual manner picture-making style, he discusses objectivity in photography and describes how the photographs are exhibited and what are the consequences on the viewer perception.

Following text and photos by Maury Gortemiller.

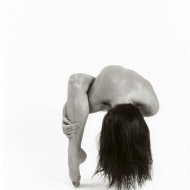

I’m interested in images of objects which have meanings previously thought to be closed. Robert Storr speaks of the estrangement of the photograph, the medium’s capability to depict persons and objects in such a way that obliterates whatever context may have been attached to them. Furthermore, when photography is operating at the highest level, context as suggested by the photographer is ambiguous, allowing the viewer to re-contextualize as dictated by his or her experiences, intuition and knowledge. In using my environment as the raw materials for creating art, I reinterpret and alter the intentionality of found objects.

The series No Anthem/Speed Queens examines the deceptive immediacy of the snapshot aesthetic. The choice of making seemingly casual photographs is bold and immediate and offers countless opportunities for re-contexualization. I’m reminded of Walker Percy’s essay “Metaphor as Mistake” from The Message in the Bottle (1975.) Percy extols the virtues of metaphor and poetic language, and in particular what might be termed “accidental metaphors.” For instance, a person might misinterpret or mishear something that someone else is saying, and come up with a new phrase or word that actually better defines the essence of what the original was. Similarly, snapshot photography, with its capability of placing images into an infinite number of contexts, can more effectively relate meanings and suggestions that are otherwise indescribable via more traditional modes of photography. To paraphrase Percy, the snapshot aesthetic is the accidental blundering into authentic poetic experience.

Art is challenging when the conceptual handiwork and craft are, on at least some levels, transparent. In such instances, the viewer is not besieged by technique or convention; rather, there is a delicate confluence of culture and history in which the viewer recognizes elements of him or herself. For Robert Adams, photography suggests that beauty is commonplace when the images appear to be made effortlessly (Adams, Robert. Beauty in Photography: Essays in Defense of Traditional Values. New York: Aperture, 2005). Beauty, according to Adams, is form, coherence or structure gleaned from an otherwise chaotic world. We equate “form” with “beauty,” he states, because doing so assuages our fears that the world is without meaning, structure or significance. From this perspective, photography is a visual palliative, restoring our collective psychic equilibrium in small snatches of light energy.

The “effortless” look of the snapshot photography accelerates Adams’ ethos. The seemingly haphazard compositions, the on-camera flash are a haphazard aesthetic, suggesting, at times, complete indiscretion and contingency. In fact, images that appear to have been made accidentally, as if the photographer opened the shutter unawares, are sometimes indistinguishable from more premeditated imagery. However, such an accidental aesthetic is paradoxical, for it is a deliberately cultivated approach. Despite the conventions of the snapshot, the best photography traffics in syncopated rhythms and tiered harmonies that arise visually from the trappings of the everyday. The snapshot aesthetic is the careful, beguiling manufacture of the contingent. Ars est celare artem.

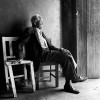

Snapshot photography exhibits fragments of beauty/order for Adams. However, I suggest that the poignancy of the snapshot is the fact that beauty is identified precisely in the overlooked, the downtrodden. The “ordinary’ is often marginalized visually, as is the commonplace and the local. This interest in marginalized subject matter has antecedents in the Historical Sections photographs of the Farm Security Administration, in which photography was used to document the indigent of the more benighted sections of the U.S. Photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Russell Lee captured the reality of poverty in the form of emotive images. Evans in particular developed a great formal variety to his photographic description, coupled with a distanced approach to the subject. His photographs probed the distinction between a document and a work of art. According to John T. Hill and Giles Mora, Evans’ search for visual balance and symmetry in his photographs was a manner of imposing aesthetic order on chaos (Hill, John T. Hill and Giles Mora. Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye. New York: Abrams, 1993). Similarly, snapshot photography often examines the marginalized -be it the mundane or the culturally “regressive”- via an aesthetic that mimics a documentary approach. The snapshot look suggests that the photographer merely pushed a button and recorded the subject matter before the lens. This seemingly casual manner of picture-making suggests that all things are equal before the camera, that everything is worthy of photographic description.

I believe there is no objectivity in photography: a wealth of information about the photographer and his/her culture is transmitted simply by pointing the camera at a certain subject at any particular moment. However, the appearance of objectivity in snapshot photography, when employed in recording mundane subject matter, can produce utterly transformative images. The semblance of a detached, emotionally unengaged style of looking de-familiarizes the ordinary, producing an internal identification with the viewer of something thought to be purely external. Objects are described as if through a funhouse mirror. I take as my credo a statement by musician Frank Black, in which he paraphrases David Byrne: “Stop making sense and have rhythm. Or have groove. Or rhyme. Or use some interesting imagery. Or be very convoluted about what you’re trying to say, for the purpose of making it interesting for all of us” (Sisario, Ben. Doolittle. New York: Continuum Publishing Group, 2006).

My images are exhibited in various print sizes, and displayed upon the gallery wall at varying heights and in inconsistent spatial relationships to each other. The viewer is compelled to move back, to physically remove herself from the wall, so that the entirety of the work may be viewed at once. She must then move closer to more fully examine the larger prints, and closer still – right up to the wall – to view the details of the smallest prints. This forced perambulation suggests the singularity of each image (up close), the relationship between adjacent images (farther from the wall), the connection between images placed apart (farther yet), and finally, the images as one distinct patchwork, a mosaic of singularities to be consumed separately or together.

This literal shifting of visual context suggests the overriding sense of displacement that I propose for the images. The scenes depicted on the wall are of immense personal import to me; variously, they may reference the particular moments in time in which the shutter exposed the sensor (in terms of my personal life or world events), the personal connection I may have with the sitter, or whom I was with when the image was recorded. The images may also signify my interest in particular colors, composition and symbols, with references to art history and popular culture. Each image is a touchstone, a node on which I, as the translator, attach simultaneously a number of references.

However, one another level, I wish the viewer to be completely oblivious to my personal investment in the work. The images must stand on their own, the formal properties engaging the viewer with little or no supplemental information. Standing before the prints, viewers begin to make their own associations with images, and they slowly connect one image with another. With no background information provided, the relationship between artist and viewer becomes one of collaboration. The viewer is literally confronted by the fact that there is no context provided for the imagery. The human mind is hardwired to seek repetition in the incoherent, to seek patterns in thought that can be related to past experiences (Sousa, David A. How the Brain Learns to Read. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2004). The viewer begins to relate the images to each other, where she is conscious of this or not. The viewer searches and discovers fragments of form (beauty for Adams) within and between images, just I discern formal qualities both in the picture-making and installation-creating.

The viewers’ associations and assumptions are as valid as my own; as the artist who placed the images on the wall I claim no privilege. The images are not mine to possess; the camera shutter was under my power, but the photons recorded are not something I “created”. It’s something I witnessed at one time, just as perhaps the next person with a camera might behold. The images are not necessarily “about” me, or my relationship to the subject. The event of the picture is not affixed to any particular context, but instead projects forward toward unimaginable future contexts. In fact, whatever claims I might make on the photographs are irrelevant, as the images drift perpetually to viewers who instill in them multiple meanings. Jacques Derrida comments on the dubious nature of authorship:

I must be able simply to say my disappearance, my non-presence in general, for example the non-presence of my meaning, of my intention-to-signify, of my wanting-to-communicate-this, from the emission or production of the mark. For the written to be written, it must continue to “act” and to be legible even if what is called the author of the writing no longer answers for what he has written, for what he seems to have signed, whether he is provisionally absent, or if he is dead, or if in general he does not support, with his absolutely current and present intention or attention, the plenitude of his meaning, of that very thing which seems to be written “in his name”

(Derrida, Jacques. “Signature, Event, Context.” Limited, Inc. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988).

The radical autonomy of the image continues to generate meaning across contexts, no matter my intentions as creator. The original context is repeated, translated, and transformed in perpetuity.

Furthermore, what I deem as worthy of recording is influenced by every other visual representation that has passed before my eyes, the anthems and tropes, but also the detritus of American culture. The entirety of history – political, artistic, cultural and personal– confluences in the camera lens. Admittedly this is a grandiose statement, which might appear to convey the photographer’s skill and originality in embodying elements of culture and art history. However, the opposite is true: at best I am a conduit, articulating imagery from, and ideas engendered, in the world at large. The photographs I produce are primarily about culture and ways of seeing first; the role of the artist is secondary. A vast network of visual imagery surrounds us, and my work simply relates and recasts ideas and images from the cultural ether.

My prints are pinned to the wall, unmounted, sans mats, frames or glass. As I am a conduit for imagery that others might also easily produce, and as these images embody ideas and associations taken from culture, I therefore do not consider my prints to be precious objects. They are paper copies in the public domain, simulated two-dimensional representations of objects and scenes themselves often already replicated many times over. The imagery itself is what is important; it is the subject and the formal properties of the images which engage myself and the audience in our respective experiences. Conversely, the paper on which the image is printed is an inexpensive, replaceable vessel. To borrow a literary analogy, the image is to the words of a poem as the photographic print is to the pages of a poetry book. Generally speaking, books are not free, but most are easily replaceable. My prints are simply an efficient means to share images in a physical environment.

The decision to not frame or mount the prints, in addition to the aforementioned variation in print sizes, allows me to fully engage the dynamics of the exhibition space. For example, prints may be pinned in a corner, or arranged around light switches. I’m able to assume a curatorial role, creating spatial configurations which may be alternately formal, symbolic or ambiguous. Images may be arranged contiguously, the verso of a print may be shown, or perhaps one print might cover another. The overall effect is one of atomization, a dispersal across the walls of the exhibition space. Each print is both singular and related to adjacent images.

My imagery is equivocal, it is of an uncertain nature or classification. The seemingly random depictions on the walls of the exhibition space approach the sublime by the virtue of their juxtaposition. In the words of Jean Baudrillard, the casual aesthetic of the images has a way of liquidating all referentials (Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulations. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995). The estranging quality of the snapshot alters the intentionality of objects and persons, often changing any meaning originally attached to them. I consider myself to be a mediator of images, a translator of perceptual phenomena. My images depict the residue of human experience, shot through simultaneously with humor and implacable longing.

You should see Maury’s work on apnea!

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.