Text and photos by Max Sher.

Map and Territory

I was born in St. Petersburg, then Leningrad, and, at the age of 11, moved with my father to Kemerovo, a Soviet-built industrial city in West Siberia. Almost every summer, I used to travel back to St. Pete to stay with my grandparents, and I remember roaming the area where they lived with a Soviet map of the city – wittingly incorrect and lacking many streets including the one where my grandparents’ house was located. It should be said that normal, detailed city maps were hard to get during Soviet era. Back in Kemerovo, there was no city map available at all until late 1990s. I started putting the missing streets on my map of St Petersburg. Then I began exploring other neighbourhoods and putting the missing streets on the map as well. I was constructing, unconsciously of course, my own mental map of the city, thus symbolically defying the State image (‘map’) of the territory.

Travel and photography change your mental image of the place. It’s a cliché to say Russia is huge and it is – in purely mechanical terms of the area it covers. But if we travel and photograph where people live and where there is culture or industry, this image of hugeness shrinks dramatically. During Soviet era, the geographical map of the ‘sixth part of the world’ was one of the sacred tools of power. At the former czar’s Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, a huge map of the Soviet Union made of gems had been installed where the imperial throne once stood. When I was kid it was still there.

The role and image of traveler and photographer in Russia also changed dramatically over the last one hundred years. The pre-1917 Russian photographers were private entrepreneurs who had a relative freedom of what to look at and photograph. Many of them produced picture postcards as part of their business, and these postcards depicted not only ‘attractive’ places but also prisons, factories, alms-houses or hospitals for the poor. This interest towards the everyday culture was effectively banned after the 1917 revolution. Photography was harnessed as a tool of propaganda and very soon, a certain matrix of representation took shape while attempts to picture the everyday routine began to be seen as subversive and treacherous. The image of the country was effectively reduced to that map at the Winter Palace. Traveling around the country became severely restricted as well. Many cities like Vladivostok or Kronstadt were sealed off even to Russians. The Benjaminian figure of the flâneur – inseparable from the image of the contemporary photographer – became virtually impossible. Moving around the country was only available to those employed by the State – military, officials, journalists, or scientists. Freelancing was illegal. Taking pictures in the street was equal to spying. All this, it seems, was one of the reasons for an almost complete absence of photographic work focusing on inhabited landscapes as a subject matter between 1917 and late 1980s. Very few images survive of how our cities looked and felt like, and changed during that time.

Today’s photographic practice still faces a lot of restrictions although incommensurable with the Soviet times. It is still technically prohibited to photograph railway bridges, for example, or to travel to the so-called ‘border zones’ without getting permission from the KGB successor agency FSB. The latter is all the more absurd that you can easily avoid it: once there, you get detained by border police, pay a 10-dollar fine and are allowed to stay on. That means still control for the sake of control.

To photograph my landscapes I am often looking for elevated vantage points. By taking photographs therefrom I symbolically appropriate, privatise the viewpoint, the image and thus the territory that were tightly controlled as recently as a couple of decades ago. At the same time, these vantage points provide the necessary distance, both physical and metaphorical.

Russia as America

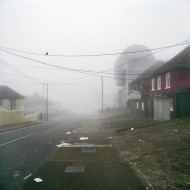

The main question of course is how to depict the Russian inhabited landscape today. I use this word – inhabited – because the term ‘landscape’ in our culture mostly refers to the pictures of natural scenery and not to places where people live. Interestingly, a Russian city is often considered ‘nice’ for the nature that surrounds it, not for urban environment or architecture. Since most of our cities are generally considered ‘ugly’, this perceived ugliness as well as many other unpleasant realities of our everyday life alienate many Russians from their own cities. We just do not consider them ours.

What I’m trying to do in my project is to bring out all the influences – from the 19 century Russian landscape painting and photography to Soviet-era postcards to New Topographics and Google Street View – that help define today’s visual vocabulary through which to look at and make sense of our landscape. What matters to me is the idea of a certain type of optics – focusing on the unnoticed elements of our living environment. It is very effective as a tool to accept and face the reality, to demystify it in a way. We need to look at our country the way American photographers look at theirs. Explore, record, accept, love it.

Strange as it is, Russia has always been at loss for a detached, calm representation of itself because of either censorship (control of the image) or over-politicising / over-romanticising on the part of both the state bureaucracy and the educated classes (as noted by Vyacheslav Glazychev1). While the state propaganda fed us with feel-good images and that gorgeous ‘map’ of a mighty empire, the ‘democratic’ image was supposed to ‘tell the truth’ or struggle for an abstract ‘common good’. I want to liberate the documentary photographic vision from both biases to aestheticise the ‘ugly’ to make it enter our consciousness. It’s nothing new, even in Russia, if we remember what the pre-1917 Russian photographers looked at and photographed. The point is: this is how Russia looks like, let’s face it, and let’s treat it as ours.

Russian Palimpsest

So, why Russian Palimpsest? The title of my project suggests an image of the landscape as a multi-layered medium, written, erased and re-written upon over time. Basically, every landscape – American, European or Russian – is a palimpsest. But to my mind, our post-Utopian territory is a palimpsest par exellence where very little ‘shows through’ after the previous layer has been erased and is being rewritten upon. Despite a thousand-year-old history, this country collapsed twice in less than 80 years, first abolishing all the institutions of the past and the past itself to form a sort of an isolated apocalyptic sect (as defined by Boris Groys2), then dissolving this sect, only to find itself between the Future where it has already been and the Past where it had already been too, completely disoriented. As a result, our landscape presents an unbelievable pileup of ill-thought-out cities, top-down development projects hastily implemented without much prior analysis, poor infrastructure, childish architecture, and that famous feeling of impermanence, precariousness, and unrootedness, so ‘rooted’ in our identity. What might be the role of photography here? Catalog it! Of course, you can never make a full catalog of anything, even less so of something constantly evolving but a catalog of landscapes is possible. What should be included in it? In Russia, as in America, the only possible catalog of landscapes, I believe, is the one compiled from random images with something more in them than mere archetypes. I’m looking for images that convey a spatial sensation of the country, when you can say: hey, that’s Russia of our time. This is what I mean by demystification.

All photographs are captioned with the name of the place, date and exact geographical coordinates suggesting an open-ended diary-cum-catalogue of our time and living space.

For more photos and stories, please visit Max Sher website.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.