Text by Marine Cabos, photos by Nadav Kander, Edward_Burtynsky and Ian Teh.

I have always enjoyed experiencing landscape as well as contemplating all sorts of pictorial representations of it. To me, depicting landscape is a mean by which a photographer attempts to understand the mystery of nature, while trying to understand his/her own place within it.

Although I do not have any kind of creative talent whatsoever, I have always been eager to watch, speak, and write about art. I guess this is one of the main reasons why I decided to plunge myself into Art History with a special focus on photography. Indeed over the past six years I developed a keen interest in photography and especially photography depicting China’s landscapes throughout the centuries.

Since then I could not stop searching for photographers that have extensively worked in China, whatever their origins. One day I came across the powerful artworks created by Edward Burynsky, Nadav Kander, and Ian Teh. When I saw their photographs for the first time, I immediately asked myself to what extend these Westerners can participate in the shaping of China’s image? One might find this question puzzling at first especially if one assumes natives would necessarily provide a “truer” gaze than outsiders. But to me (as for many people specialised in the field of photography of China) there is no such thing as a consensus in what constitute core elements of ‘Chinese photography’; instead I am more interested in the variations of photographers’ gaze through the depictions a common subject matter.

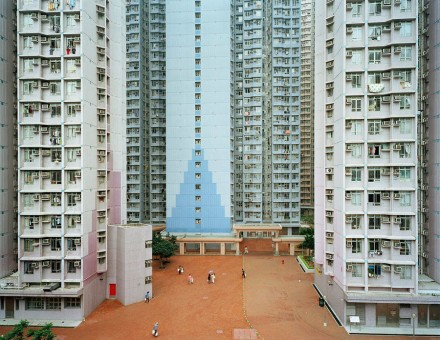

These three photographers created compelling images representing China’s landscape in its largest sense. By that I mean their notion of landscape does not only refer to the natural world, but also to places that range from man-altered to industrial zone, cityscape, cultural landscapes and other types of sceneries. Let me introduce briefly what they managed to photograph when they were in China.

Over his twenty-five years career, the Canadian Edward Burtynsky (born in 1955 in Canada) developed keen eyesight of man-made alterations upon nature caused by the pursuit of modernization, which he conscientiously captured across Northern America. Burtynsky’s anxiety to engender the audience’s awakening of such disrupted sceneries leaded him to China, where he engaged in a series of photographs depicting human and environmental costs of the tremendous economic boom China is undergoing. For five years starting from 2002, Burtynsky explored the ‘Middle Country’ by scrutinising on the one hand the urban revolution with his series Urban Renewal, on the other by following the industrial production processes: from the collection of energy with his series on the Three Gorges Dam; the human labour with Manufacturing; the steel producers with Steel and Coal; the collapsed heavy industry due to mid-90s restructuring with Old Industry; the ships production in ports with Shipyards; to finally the recycling process with Recycling. His large-sized photographs offer a paradoxical commentary vacillating between deadpan and bleak impressions on the China’s changing landscape.

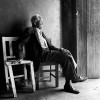

Regarding Nadav Kander (born in 1961 in Israel), his contribution to the shaping of China’s landscape was also significant. His Yangtze series – which resulted from five trips initiated in 2006 – shows an interesting account that mingles the pictorial tradition of portraying the river sceneries, and an unavoidable social commentary about the unnatural development within natural settings and its consequences on the population. Although he tried as much as he could to maintain a distance because of his awareness of being an outsider, Kander ultimately re-enacted individual and collective sentiments of rootlessness commonly felt by not only the Chinese he met, but also himself as an Israeli-born South African living in England. His photographs propose a journey navigating by the river on traditional boats, walking across broken bridges, ending in nearby cities with leisured people.

Finally, the Chinese-British Ian Teh (born in 1971; based in London) also experienced China since 2006 through a solo initiatory journey in which he wanted to discover the industrial hinterlands. His series Traces: Dark Clouds offers photographs of Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Liaoning and other provinces across China. Teh chose these specific places for they revealed another side of the so-called ‘China’s miracle’: the environmental sacrifices of perfecting the country and their side effects left for the future generations. Apparently Teh continues to work on China according to three of his projects entitled Merging Boundaries (in which he looks into the Sino-Russian and Sino-Korean limits), The Vanishing – Altered Landscapes and Displaced Lives on the Yangtze River, Tainted Landscapes 1: Birth to a New Coal Power Station, and Tainted Landscapes 2: Heavy Industry in Linfen, China’s most Polluted City.

It was quite a shock to discover their work; needless to say that I immediately fell in love with them. At that time I just arrived in London and I was visiting randomly galleries near Old Street. I ended up in the Flowers Gallery where I had the chance to meet Chris Littlewood, the Director of Photography. I talked about these three photographers (who were all exhibited at least once in the gallery) and asked him if he thought they were creating divergent and/or similar representations of China. Chris replied that:

“On the one hand they obviously explored a common subject, yet all possess a different gaze. Kander for instance took a very indirect, poetic, personal approach opposite to documentary considerations. His Yantze series reflected an atmosphere that embraced a wide range of sensations and feelings, such as alienation or sadness. Contrarily, Burtynsky’s gaze is direct, almost rough, highly distanced – literally and judgementally. The magnitude of his panoramic photographs mingled documentary and pictorial approach to landscape through which he strived to provoke sustainability awareness. As for Teh, his method to first spent days in the place in order to gain trust and proximity with the people, then taking photographs recall somehow journalistic practices. Ultimately, the trio engaged in a ‘China-centric’ photographic dialogue that possesses highly intuitive and pictorial dimensions, thus leading the viewer to be visually overwhelmed and trapped.”

Chris’ insightful comments enhanced even more my passion about landscape photography of China. In truth although these three photographers belong to different cultures (thus assumedly possess dissimilar cultural conditioning) they nonetheless share astonishing similarities. First, they reify the timeless Western attraction for China cultural and aesthetic paradigm. Second, all combine with verve highly aesthetic and documentary-inflected viewpoints so that to create panoramic photographs, which transform urban or natural landscape into paradoxical sites of quietness, unsettledness, alienation, and sublimity at the same time. Third, none of them dictate an easy answer to such destructions; instead they aim to leave the spectator free of deciding whether there is any ethical implication.

Rather than affirm their gaze as condemnations of Chinese harsh disruption of either natural or urban landscapes, they have chosen a more insightful path in problematising their photographs’ capacities of showing diverse intuitive and emotional responses to another culture environment, which eventually appear relevant in both Chinese and global contexts. Ultimately I also believe Burtynsky, Kander and Teh shed light on the existing links between China and the West.

For more visual stories about China, please visit Marine Cabos Photography of China.

An amazing selection of photographs. Both lyrical and monumental in scale.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.