Text and photos by Steven Nestor.

We are now universally used to and expectant of the perfect, pristine world that digital affords. For most consumers it is the only tool for photographing. If even considered, film is largely seen as being cumbersome, limiting and firmly consigned to the past. It was what most people’s early life was recorded on and certainly not part of today’s world of PS, delete or upload. When I asked 16-year-old summer students of mine if they had ever shot film, their faces frowned in puzzlement.

“You mean that thing like a little tube you used to put in the camera?”

“Yes.”

“No.” A firm answer, but still confused by the oddity of the question. It was as though I had asked them if they still drew their water from a well.

Digital is the now, without beginning or end. There is no ‘first’ or ‘last’ image. The file numbers can go unnoticed behind concerns about pixels and megabytes. Moreover, the numbers 0, 12, 24 or 36 are utterly meaningless to most who now photograph.

When starting out in photography I avoided winding the film on to the camera dial’s first setting of frame ‘1’ so as to maximize the number of images I could take on this “little tube”. It was satisfying to squeeze as many as 39 frames out of a single roll of 36 exposures. A small victory for the dilettante. The minor risk of course was that the first frame might not “come out”. At the time, however, I don’t recall checking my negatives to see why. With an envelope of prints in the hand, that first image was either there or not. Sometimes though an overlooked sliver of an image had made it onto the negatives. Even if I did notice something was there, my eye would have skipped over it to the first complete frame.

In the early years of my photography good labs were hard to come by and the results very mixed. Scratches and fingerprints on negatives were more often than not the norm. Similarly, green, red or cyanic prints were easily explained away with the magical words, “It must be the film”. What did they care?

But what happened to those first frames? Sometimes in cocking the shutter I must have wound the film just enough and missed losing the frame. On other occasions the lab may have decided to cut it off from the strip as it was “ruined” anyway. What customer would want a half burned print? The larger commercial labs would even sometimes put a small removable sticker with helpful hints onto prints showing signs of motion blur etc. Then I bought a new Nikon and ditched my old Pentax. No more manual winding. No more half frames. It automatically wound on to ‘1’ and ended at ‘36’. The shot that might not come out was eliminated. A sort of semi pace towards digital was being made in the late analogue age and the reward of getting more frames out of a roll was forgotten. I had moved up a ranking in the amateur world where equipment takes precedence over vision.

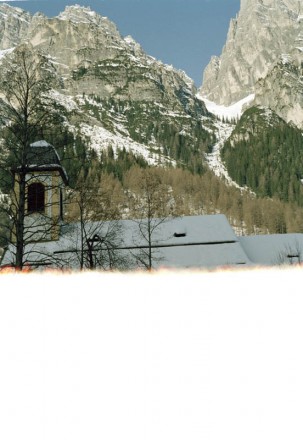

It was not until a few years ago that I was trawling through old negatives looking for images from the early 1990’s that I noticed one particular image that I had never seen before. Half of the subject – a friend in Germany – is lost in unintended exposure of the film to daylight so that the frame would have been automatically discarded in the printing process. The result is a sort of double exposure where daylight has insulted on the negative and burned off half of the frame and subject, never to be retrieved. Unmediated by lens, aperture or speed, light has triumphed destructively and a kind of ‘pyrography’ has emerged.

As a result of this find I starting using a fully manual camera more prolifically again and so automatically reverted back to trying to maximize the number of frames I could get out from a single roll. The first frame, happily compromised again, could now in many ways be the most flawless of the roll. It is also the perfect expression of analogue, of photography, of light and of destruction. And I have continued on and off with this deliberate hit and miss procedure. Either the frame is perfectly compromised or skipped. About a year or so ago I decided to examine all of the “lost”, half burnt frames I had and to see what, if anything, they might collectively say despite the diversity of time and subject matter.

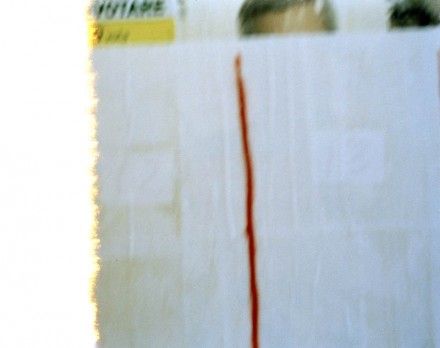

Putting together this body of work I wanted to go a step beyond my fascination with old found photographs with their nostalgic and portal qualities. When working with the archieved image there are the usual questions surrounding it’s provenance, production and the issue of to what degree one restores the image. Here, however, the damage occurred at inception when I unconsciously – later deliberately – created seemingly meaningless partial frames to be later discarded. What attracts me beyond the age and personal connection to these images is the pronounced and profound element of light, which is normally and deliberately shut out for all but the briefest of moments. Whether a glow on the edge of the frame or near total erasure, these scorched images – these brilliant half-worlds – represent a moment that has been taken, that has been recorded: a singed fragment snatched from the destruction of a pyretic light.

Producers of film have always pointed out just how stable the medium is and how pigments will last for well over a century. However, the message on the box reads, ‘load in subdued light’. There is that risk of accidental exposure, of ruining the film. Light – the very basis of photography – is dangerous to the recording material. If uncontrolled, it wipes the film clean in one scorching instant, thus also obliterating what might have been a perfect frame, memory aid etc.

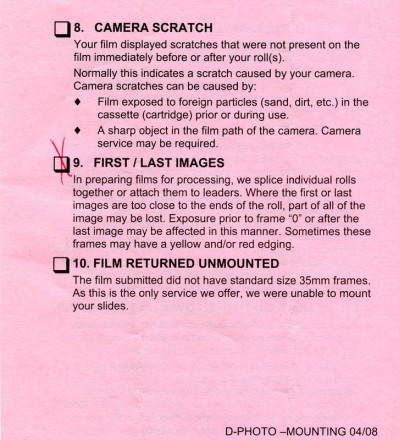

When initially squeezing in those extra frames I was not trying to make any sort of statement. It was when I examined that image of my friend in Germany that I saw a value and new reading of these first (and last) images. Many of these images, such as my first ever one from Austria in 1992, were only given life (or another dimension) through their partial destruction. Later, I could be deliberate with my film loading and imagine a possible reading, should the frame burn as I wanted it to. The first deliberately seared frame to work the way I hoped was that of the main railway station in Turin, taken on Kodachrome 64. I can read it – enjoy it – on a purely superficial level, or, given that it is the last year of Kodachrome, see it as a comment on the end of a specific era as well as reflecting on the fragility of the present.

This semi-erasure also captures the essence of how memory selects and sorts. What did I remember of a day trip to San Marino in 2006? Shafts of light through a non-descript church window. A man with a placard protesting his innocence in front of the palace. This almost completely erased frame of the San Marino landscape perfectly illustrates to me that vague, faded memory of a view I had stopped to photograph, to snap. It is confirmation that memory, in unison with time, is forever falling from our grasp and from what our eyes are projecting inwards. Although by depressing the shutter release we may be pausing time continuum, by also including the moment of destruction these images challenge the delusion of the alleged power of photography to halt time, to preserve memory.

While seemingly bland, even completely pointless, the most recent ‘first frame’ was particularly pleasing to produce and offered far more than I had imagined when standing in front of the subject. Firstly, there was the intrigue of encountering the Safe Surrender Site in the small mountain community of Groveland, California. Here an unwanted baby may be surrendered within three days of being born without fear of prosecution. Obviously there is an official sign indicating the presence of a surrender site, but what did I actually see and remember? What might the mother recall of the site when abandoning her baby? The sign? Or maybe the neatly coiled umbilical like hose at the side of the fire station? This resulting half burned image testifies that I was at the site, framed and recorded it. However, I only remember that hose. That’s what struck in my mind. And that’s what was left in the recording process. That neatly coiled hose descends from a permanent erasure.

Going through my 30+ images I was reminded of another facet to this work. As many writers on photography have pointed out, the specter of death is something we experience when reviewing photographs and catching a glimpse of where we are going by seeing were we no longer are. Here, however, that flicker of the end has been at once augmented and usurped. Not only is there that eternally snatched moment from the past, but there is now a new dimension: the eternal moment of destruction of the film and partial erasure of that which has been framed. Although there certainly exists a link between the specter of death and photography, these first (and “last”) images also contain in equal measure both destruction and a curious chanced beauty. The coincidental burning of the frame and the moment tempers life’s moribund condition and animates that spared fragment.

Because, like us, film is physical, delicate and subject to aging (rather than corruption in digital), and because life has only one conclusion, I feel that these compromised moments are the more beautiful for it. The message cannot be said to be exclusively one of demise; rather it is the curiosity of the partially singed frame, the partial recall. The destructive and unregulated element of light animates this otherwise ‘flat death’, sending a spike into the two-dimensional plane. While the chance or deliberate ‘yellow and/or red edging’ can be read as a manifestation of a loss of memory and time, it is also death’s competitor through a beautiful distraction: thus, distraction via destruction. It is now (and for the lifetime of the eternal moment) a new first message, obscuring what is usually reserved for primacy of place.

When digital first arrived I offhandedly rejected it. For me it was cheap and nasty and I became immediately despondent for the seemingly immanent demise of analogue. However, digital’s near complete dominance of the photographic world has conversely injected more life into analogue than analogue itself could ever have done alone. Analogue’s great “nemesis” has pushed the user closer to their preferred medium, prompting a fuller exploration of film as seen for example in the work of Miroslav Tichý or Tacita Dean. Those still choosing film over digital are free to embrace and exploit its physical limits and flaws, whereas in the past such compromised frames as these First/Last Images would more likely than not have been rejected out-of-hand or cropped to exclude the unwanted “damage”.

Please visit Steven Nestor website for more photos and stories.

Remember seeing this on my film strips. Miss them……Really good thoughts and article! Sharing on FB…

Thanks Loretta for your comment/feedback (& FB share!). Steven

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.