Text and photographs by Ryan Lobo.

I am in Liberia. Eric Strauss, Danielle Anastasion, Ryan Hill and myself are making a self funded independent documentary film called “The Redemption of general Butt Naked”. The film is now complete and has been invited to the Sundance film festival in Park City Utah and is in the running for best documentary feature at the festival.

We are telling the story of Joshua Milton Blahyii, also known as General Butt Naked, a former warlord who terrorized Monrovia for many years with his child soldiers, murdering, raping, cannibalizing, maiming and brutalizing thousands during Liberia’s civil war. Suddenly in the middle of the fighting and at the height of his power, Joshua claims to have had a revelation from God and laid down his weapons and renounced violence. Many years later, now a preacher, he returns to Liberia to begin “a crusade” to redeem his past. We are with him when he does so.

The American Colonization Society founded Monrovia in 1822 as a haven for freed slaves from the United States and the British West Indies. It was named after James Monroe, then president of the United States and was founded on the premise that former American slaves would have greater freedom and equality in “Africa”. The freed slaves brought with them Christianity and created Monrovia but did not integrate with local tribes which had dealt in slavery for a long time, selling their own people to slavers from Africa, America and Europe. The religious practices of the Americo – Liberians have their roots in the churches of the American south. These ideals influenced the attitudes of the settlers toward the locals and the Americo-Liberian minority dominated the native people, whom they considered primitives. The immigrants named the land “Liberia,” which means “Land of the Free,” as homage to freedom from slavery. Who the freed slaves enslaved and exploited was a different matter. A military coup in 1980 overthrew the president William R. Tolbert, which marked the beginning of a period of instability that eventually led to a civil war, which devastated the country’s economy, left 200,000 people dead, tens of thousands mutilated and most of the female population sexually attacked in some form or the other.

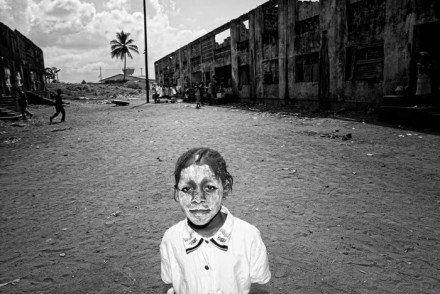

Many of Joshua Child soldiers live in Xolalli, a slum (now razed) that translates to “Where death is better than life”. Addicted to heroin and with intensely traumatic upbringings and histories Xolalli is where the most desperate, the most hurt and the most broken people reside, according to Joshua. We leave for Xolalli with Joshua and his wife Josie.

We walk in and Ryan films Joshua meeting with a lady whose brother he had murdered. We enter on foot and after awhile things go a bit out of hand. We had asked a few of the local guys to help us ask some of the slum dwellers to move downstairs to give us some silence and things get rough when the “helpers’” start yelling at people. Joshua apologizes at length and the lady accepts his apology. She tells us that she forgives him as it is the past and because he has earnestly appealed to her. Just like that. The previous time we had visited Xolalli it had been a little different. An excerpt from my journal.

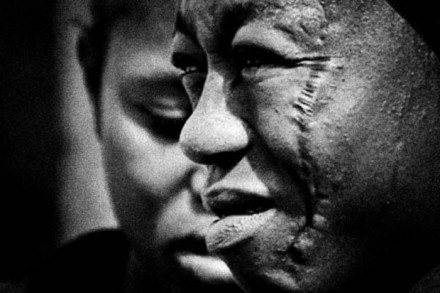

“A woman emanates from the shadows screaming at him. She has a terrible scar on her face . She sobs that the general has killed her brother. She points her finger at Joshua and cry’s out not words but sounds of grief and horror at seeing him. Joshua says “I am sorry. I was not the person I am now, then I did not know what I was doing.” She calms down and puts her head in her hands as Joshua begs. Men silently surround us. I take a photograph. Finally, she places her hand on his shoulder as he touches her feet and leaves. I feel like I have witnessed something immense. Joshua tells the story of how he killed her brother and then ate his heart because he spoke French as one of the factions the general fought against then spoke French. People who have truly suffered do not seem to find it difficult to forgive. Out of suffering and sorrow endured seems to sometimes come a deeper understanding of forgiveness and the shortness of life. Or maybe it is just a terrible fatigue.”

We leave the interior room and I stay there while the rest go off. In seconds a group surrounds me. One says he will take the camera and smash it on my head if I take his picture. I smile. Things get worse. They push and walk me into a corridor. After awhile one says he likes my hat and shoes. They are high on heroin. One asks for money. I say I don’t have any. They get in my face. I am very afraid but pull off the nice guy, I am here to help you act. One guy looks like he has a machete in his pants. He does.

I am going to get robbed or worse I feel. They egg him on. I take his picture. I say that I will make them famous and put them on the cover of National Geographic. They like this and suddenly begin to pose with me. I am afraid but also calm. When I raise the camera I find myself automatically watching myself as well as the exposure and composition. I watch my fear from somewhere else and am almost amused at my own terror when I look at a photo I have taken. It’s all over my face. I find myself laughing. Thank God for digital.

I squeeze out and two guys in football shirts approach me and tell me about a sick child who needs my help. I think they want to get me away from the rest of the crew. I feel my insides implode. I rush off to where the rest of the crew and Joshua are further down the street. Crowds hem me in and push me. Guys are going wild and things are slipping out of control. I walk slowly to Eric and Eric says we have to leave. A riot is beginning and we are the focus of it. We leave, trying to walk calmly with yelling and screaming all around and the car is not where it should be. He has parked further up the road. A crowd follows and they are very angry. They ask for money like it is owed to them. The general is talking to them and he seems to keep himself between them and us. I decide to hit the first person that goes for me with the camera. I change lenses, as I don’t want to ruin the wide lens and replace it with the 35-70 as I walk.

They follow us on the road as we walk away screaming and yelling. “You come here like this and just leave man…show some respect, I want something from YOU.” Such a sense of entitlement. It was to be a recurring Liberian theme during the process of film making.

Joshua promises food for the people at Xolalli and on compulsion Eric, Joshua and myself stay behind and the rest leave in the car to buy rice. Later we walk back to Xolalli from the car, with Joshua and the rice that has just been bought. People are fighting and screaming. A tall guy warns me not to take photographs.

Guys come up to me and ask for money aggressively. Women are given food first and the lady whose brother Joshua had killed, comes to the front of the line shoving and screaming for her quota. Women fight and grapple behind me. I am hemmed in. A man is stabbed but I don’t see it and hear about it only later from Joshua. I talk my way out of some things. I stay close to the general but he has problems of his own being inundated with people.

He pauses in the middle of the chaos and is silent.

Joshua makes a phone call and in 5 minutes about 10-15 guys from the “forgiveness rally” land up. They help organize things and after awhile some of the young men go crazy and Joshua tells me to get into the car “now”. One of the guys is frothing at the mouth. Taking a picture now might not be the best thing. I put the camera on the floor and put my foot on it as they try to grab it through the window. They are all over the car running alongside it, banging on the windows and trying to grab at stuff. One jumps on the car as we drive off and hangs on for a while before dropping off. He shouts when he hits the road.

After this we go to the church to wait for Pastor Kun. I decide that if the UN pulled out, this place would go to hell very soon. I wonder at the systems people have faith in here. The church to some could be a refuge. They are no other functioning systems. No justice system or properly functioning rule of law. No trustworthy government, yet. We horse around in the church. Joshua jokingly tells me he will cut my d— off as his wife says I am cute. I pose for a photo with them and he suddenly lifts me up over his head. It is awkward, this new familiarity and I laugh as he lifts me because I really don’t know what else to do. He is incredibly strong and I imagine what his strength could have done to women and children in the days when he killed and tortured.

At night Joshua emails his mother some photographs I took at the forgiveness rally he had organized the previous day. I type for him on my computer as he dictates.

Dear Mom,

This is the rally for acceptance. We appealed to the society yesterday for every harm the child soldiers has caused. We took the blame because we were the ones who forced them to take arms. Now we do not feel better that the society accepts us and reject them. We appeal to their parents and relatives to please accept them and made them to confess their sins openly and appeal for forgiveness. Fifty of them are accepted by the church and they are trying to cater for them. The church in Liberia is not strong yet but they are trying. Mom it was touching yesterday when the society came embracing and accepting their children again. I wish I could put these guys in a home and get people to train them. I am feeling really good! Love you mom,

Joshua and Josie

Danielle chats with Joshua and asks how he felt when people were screaming when he killed them. Joshua said he didn’t think he was doing anything wrong and spoke of how he had been conditioned to do the same since he was 11.His father was a high priest of the Krahn tribe and he had taken part in many human sacrifices including those of children. He would swim out into rivers and drag swimming children into the depths where he would kill them. He said he initially thought that Jesus was just another powerful deity and that he had chosen Jesus, as he thought he was more powerful than his deity. Initially.

Joshua tells me about how spirits can latch onto vulnerable people. He tells me about his astral traveling and how he would lock himself in a room when he astral traveled because if his body was moved, his spirit would not have found the body again. He would astral travel and latch onto other people and tie up their spirits so that they would be comatose in the morning. He tells me of haunted houses where spirits would not believe themselves dead. And of the people he murdered then and about the scar on his forehead. About spiritual attacks on him and that they were actual physical attacks. I ask Joshua about his dreams and he says he recently had a terrible nightmare where the ghosts of people he had killed were trying to kill his children. He would carry them through a house trying to evade the spirits who wanted to kill them.

Today we are to film Joshua’s baptism. We meet Doug an Aussie preacher who is to do the baptism and drive down to the beach at 14th street. Doug according to Joshua has been preaching in Liberia for 51 years. Joshua considers him a mentor and a great man. He gives Joshua instructions to close his eyes and fall back into the sea. Doug reads from the Bible about how Paul persecuted the Christians but came over to Christ. Joshua listens carefully, slightly hunched and respectful. He is baptized. He suddenly runs into the sea and swims through the waves.

We head to the “Africa Hotel “post lunch to shoot the master interview. It is unbelievably hot. The building has been destroyed, cannibalized and abandoned. The jungle grows into rooms here. It creeps in.

The interview is cut short by rain. Joshua is asked questions about what he did and how he feels about his personal accountability. He says that he was in the control of spirits and his way of life then was all he knew. He would do anything for his deity. He felt all people belonged to his deity. He is not at all hesitant and does not blink when he answers.

A Journal excerpt.

“There is something dark here that is primitive, violent and expressed openly. Our so called humanity of the “west” sometimes obscures these dark parts of our nature whose existence we reject and thus allow for them to manifest in so many ways. This idea of an island, where we believe in judgment days and paradises, “end times” to misery and perfect countries for freed slaves. We want to believe in universal peace, justice and goodness. The truth is that our existences are circles of shadow and light, murder and forgiveness, peace and war. Our deepest most primitive archetypes come forth and are as much a part of us as we believe they are a part of our enemies. It will always be no matter the islands we imagine. Our history is more gigantic, more beautiful, and more terrifying than what we know of it.”

We drive back after the interview. I sit in the car with Joshua. Hours of recounting his crimes seem to have drained him. We head to the building by the bridge he once controlled and shoot Joshua recounting the battle. He tells us how the warlords he fought against Prince Johnson and Charles Taylor had all the food and how he would cut up human corpses for food. In the distance stretches the bridge so many people died upon. A child stands in the shadows. I take a photo of Joshua and the kid in frame. Joshua walks up to the child and says “strong man” and shakes the child’s hand. Ryan films.

“The banality of evil” is a phrase coined by Hannah Arendt that was used to describe how the greatest evils in human history were not executed by psychopaths but rather by ordinary people who accepted the premises of their state and participated with the view that their actions were normal and ordinary. People do not have faith in systems that do not deliver justice and jail terms to perpetrators, no matter how good they might turn out eventually. However, disease, war and horror weren’t the only things that exited Pandora’s box. The last thing to exit was hope. If someone as atrocious as the general can attempt to redeem himself, regardless of whatever idea of justice prevails or its execution and regardless of the good or bad opinion of anyone, there is hope. Before he begs for forgiveness, he had to forgive himself. Healing comes with confession and then hopefully, forgiveness. Healing for all sides.

And that is hope. Maybe for all of us.

Please visit Ryan Lobo for more photos and stories.

These are really very interesting pictures.

Amazing story and photos.

Fantastic document

Excellently written heart wrenching story with great photographs.

All the best for the nominations.

You have photographs and everything and still its hard to digest the fact that this is indeed a true story. Makes you rethink about everything that you believed in.

Extraordinary story, pictures, and courage. i get a more vivid sense of the courage of everyone involved and the danger of the situation than the positive impact of the “forgiveness” rally. Still a compelling story that should be shared. I’m looking forward to seeing the documentary.

Ryan,

God Bless, take care. Continue with the work of creating awareness.

David

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.