Text and photos by Stuart Freedman.

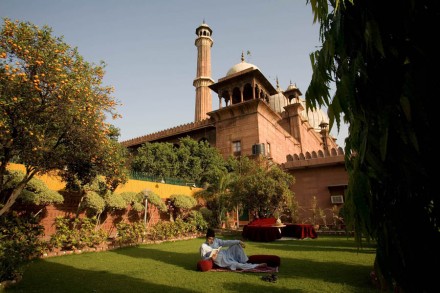

Delhi, one of India’s most polluted and brutal cities, is rarely thought of as a place with an abundance of scenic beauty. However this, and all the previous cities of Delhi have had extraordinary links with gardens and green spaces.

In this work I have been trying to image the city in a new way: an attempt to show the city without the clichés of traffic, extreme poverty and affluence. Over the last two years, I’ve tried to use Delhi’s gardens, plants and green spaces to give me an insight into the lives of its people in a way that reflects the changing India and how the city’s relationship with nature has endured in some of the most surprising places.

These gardens – these greens spaces – are a pause in the city allowing a dialogue between what Delhi was, what it is and its ever changing people. Delhi has always been a city of migrants. Every peasant that comes shoe-less to Nizamuddin railway station from Bihar to build the new ‘Shining India’ brings with him the memory of the quiet of the fields of his village. His garland offering at a shrine is his version of the planted garden in affluent South Delhi. The memories clash and mingle with the previous generation’s space and greenery and those layered memories build what Delhi is becoming as a city.

Gardening has been popular in India from ancient times. The Mahabharata, the Ramayana and the Kama Sutra all have passages that describe and recommend gardens and their layout. It is said that the Buddha was born under a peepal tree in a garden and the Bodhi tree under which he attained nirvana is holy to Buddhists. Islam has always had a fascination with the garden and Delhi, always a Muslim city at heart, has many fine examples of Mughal gardens. It is certainly true that gardens provide a secular space in the city and in an increasingly divided India where some see its minorities as a threat, (particularly) Sufi shrines attract worshippers from Hindu and Muslim backgrounds seeking solace and offering prayers.

The creation of ordered European-style landscapes was pivotal to the process of colonization and it was against this backdrop that gardens emerged as a cultural symbol of British control. The Victorian ideals of parks as ‘improving spaces’ were key as were the design of Lutyens’ wide boulevards. Functional on an impressive scale to show the city’s inhabitants who was in control they further facilitated movement of troops and traffic where needed. In that sense, the colonial space sent conscious and unconscious messages to the locals and the English alike. The ordered plantings of Western gardeners, influencing a generation of Indian gardeners, have worked in that tradition: trim hedges, cut grass that are still seen all across the Bungalow zone of New Delhi.

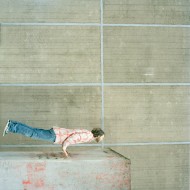

Indians have an interesting relationship with what little personal space they can occupy. People are literally squashed together and nature often breaks through the grim surroundings. Many plants and trees (some holy to Hindus and Muslims alike) are cultivated in the most bizarre places. At the edges of motorways and between illegally built structures, people tend to nature. Whilst working on a television documentary about water in the city, I noticed that in a slum where we were filming, many of the residents had roof gardens full of plants. This when they had open sewers and no running water. Returning to photograph them I was struck by the way in which plant pots, artfully arranged, somehow made the difficult surroundings a little more liveable. A shy housewife told me that she took pleasure “… in seeing the plants grow like my sons…”.

For myself, Delhi’s gardens are everywhere: in the weeds by the choking roads, the flowers on a woman’s sari and in the garlands left rotting on the streets, forgotten yet somehow revered and certainly not removed. For this work I’ve also tried to show the chaos of Delhi (and indeed India) in a way that I hope reflects the triumph of nature reclaiming the streets in an arbitrary way – much like the jungles reclaiming lost temples in the work of Kipling’s Jungle Book.

Every morning across the city, people are woken by the cries of the Mali (gardener) on his pushbike offering his services for the day. More modern and affluent areas often have roof terraces, and among the rapidly expanding middle classes gardening has ironically gained popularity again, as it gives a touch of respectable homeliness. For this work, I’ve also spent time at society parties where silk saris flit effortlessly amongst banks of the most extraordinary explosions of floral colour, the flowers themselves almost lighting the event as dusk settles.

Delhi-wallahs have come to utilise the streets’ trees as shops and workspaces. Kishori Lal a tailor originally from Rajasthan is typical. He has worked under the same Ashoka tree in New Friends Colony for twenty two years. “There was no footpath here then. The tree that you see on the footpath is standing on a narrow strip of land between two sewage lines that run underneath. I asked the maali (gardener) to plant it there and got the sapling for him. If I have any trouble, the saheb helps me out. After so many years here, like this tree I have also taken roots in Delhi. But who belongs to this place? Even the sahibs are from outside”.

For many though it is the parks that offer a microcosm of Delhi life. The New Delhi Municipal Council maintains one thousand one hundred and seven acres of greenery. One of the largest parks in New Delhi, Lodi Gardens, is a sprawling hundred-acre site of trees and lawns and the tombs of the Lodi Sultans. Here one can find cricket matches, sellers of all kinds of food and all kinds of Delhi-wallah at play regardless of class. It’s the parks that somehow give a vital clue to this work, so far unfinished. In a conservative city that has little privacy, parks are quiet corners where lovers can meet and it is here that private dramas are held in public.

Public spaces, private lives.

good post , photos ok 🙂

Dear Mr. Freedman:

Your comments & ‘Garden Images’ are indeed a much appreciated Delhi perspective.

Yours truly,

Susan Kemenyffy

I am planning to visit the Mughal gardens at Rashtrapati Bhavan in a couple weeks, but read in a news article that cameras are not permitted. How did you manage to get a photo? Can special permission to photograph be obtained, and if so who would I contact to get it? Nice photo, by the way.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.