Text and photos by Sheila Zhao.

To move. The process is mysterious. It is impermanent. It is addictive. There’s an ephemeral beauty about the process of moving that has enthralled people throughout the ages. 19th century Scottish poet, Robert Louis Stevenson, once wrote: “For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go…the great affair is to move.” That, too, is my obsession and an idea captivates me.

But how do you translate a concept that embodies a deluge of complex meanings and feelings into a series of still images? The mere notion seems like a contradiction.

It was under the most mundane of circumstances that I began my project Shifting Focus: China Roads. I have been living in China for the past four and a half years (two as a corporate drone in the public relations industry, and two as a freelance photographer). During that time, I had been very privileged to have had the opportunity to travel through some of China’s furthest reaches – from the wild, dusty expanse of the Taklimakan Desert to the poetic karst mountains of Guangxi Province. During these trips, getting to and from the various locations almost always involved overland travel, and most often, on a public Chinese bus of some deviation.

And so, in August of this year, I embarked on another trip, this time through China’s southwestern Yunnan Province. My original plan was to travel overland and head northwest, from the bustling provincial capital of Kunming, to Chengdu, Sichuan, via the towns of Lijiang, Shangri-la, and Litang. The road would take me into the southeastern edges of the Himalayan range, before entering the Sichuan basin and into Chengdu sits.

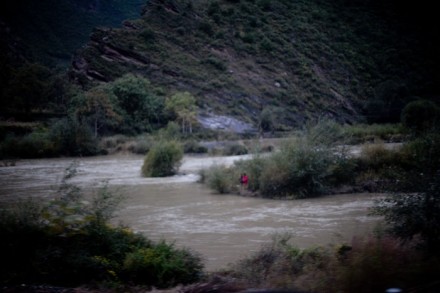

My very first leg of the trip – Kunming to the popular tourist town of Lijiang – would take eight hours in a Chinese version of the Greyhound bus. It was an early morning affair – the bus left at 7:30. The summer monsoon was in full swing and gray clouds, swollen with rain, loomed low as our bus pulled away from the terminus. At the time, the land surrounding the bus station was almost stripped bare. As part of a citywide infrastructure upgrade plan, the whole area resembled one big construction site. Migrant laborers lulled in the early morning light before beginning another day of backbreaking work. Support columns for would-be expansion bridges sat obtusely in the most unlikely of places, with iron rods still protruding from their sides.

All this – as seen from a bus – seemed very otherworldly and it was a rather natural reaction to start photographing. Only from there, I never stopped. I soon became fascinated with the views that were rolling past me, at how the land was changing, and at how the people were changing. The more pictures I took and the more I mulled over what it was that I was seeing, the more interested I became in this whole idea of changing and of moving. I also began to think of how to execute and organize these pictures into something more coherent and more meaningful while maintaining the essence of what I was experiencing.

In the end, I decided to go with the most organic approach: to record the vast expanse of land that I was passing through as it was, from beginning to end, unfiltered in its flaws and beauty, as it was shown to me through my travels. This fact would be further accentuated in the editing process, which I would organize chronologically and let the land do the story telling. Through this process, I hoped to weave a portrait of China – to show this country, this massive entity of 1.3 billion people, changing before one’s eyes in all its simplicity.

Of course, it can be argued that this idea did not reek of originality. Photographers long have made images from the window of their vehicles. The most notable of such, Paul Fusco, whose work from the Robert Kennedy funeral train, is one of my favorite bodies of work and one which never fails to inspire me. That said, I believe wholeheartedly in my own project because being able to move and to document the subtle changes of this land is in a way, my own exploration of the country that I now called home.

This past October, I returned to Chengdu, Sichuan, to start another month-long trip with a writer friend from Hong Kong. Our trip would take us from Chengdu east, into the Rouergai Grassland, then west again into the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, before traveling south onto the legendary Sichuan-Tibet highway and back into Chengdu.

This time, I had a clear vision of how to continue with this project. However, difficulties arose almost from the onset. For starters, compared to the relatively populated province of Yunnan, most of the regions on our latest trip were very sparse. Dramatic scenery dominated the trip – some of the tallest peaks and mountain passes in China outside of the Tibetan Autonomous Region towered in this part of the world. This also meant few people were willing to risk their lives living on such unforgiving land. Secondly, autumn time in Western China is gorgeous – big blue-sky days with brilliant sunshine, not a cloud in the sky, and a crisp breeze that cuts through the afternoon rays. Unfortunately, the days were so beautiful that it made for terrible light (the higher altitude only accentuates this fact). Lastly, at any point of this project, I was constantly at the mercy of fate. Whenever I booked my tickets, I could not guarantee myself a window seat, much less being on an aisle with good light or interesting views.

But that said, which projects do not hold challenges and difficulties? For me, this entire project is very much an experiment, and all these challenges came within the parameters of that experiment. My solution? To try and leverage the best lighting conditions whenever possible.

One day, we boarded a local bus from the small market town of Ganzi that would take us to the gateway city of Kangding, a trip that would last a total of 14 hours. As our bus bounced through the grassland in the pre-dawn dark, I was the only soul awake in the entire bus, aside from the driver. My eyes still felt heavy from the night before, when I only squeezed in a few hours of rest, but my adrenaline was rushing and sleep eluded me. As the first sign of morning began to illuminate the eastern horizon, we drove past a placid lake. Framed by red-clay mountains, the lake’s water was the color of a deep sapphire blue. It was one of the most beautiful sites I had seen during my entire trip and I was able to catch a few fleeting glimpses of it before we moved on.

One of my favorite authors, Jack Kerouac, wrote in his legendary book On The Road: “Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life.” And so, it is for the road whom this project is dedicated to. It is for the few seconds that I catch sight of a sapphire blue lake that I live for. That is why I cannot stop moving. That is why I am addicted.

For more informations and photos visit Sheila Zhao website.

I would like to see your pictures especially the sun.

Just curious.

Lourival Amorim

Brazil

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.