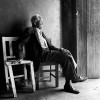

Samuele Piccoli works mixing photography, photocopies, transfer techniques, collage and painting. The transfer of photocopies of photographs on drawing paper, using cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene or acetone, creates images with a pictorial look that I find very interesting. Samuele Piccoli then adds onto these photocopied photos some external elements, be they purely pictorial, collage, hand drawn, or brush strokes. He creates images which are half way between photography and painting, pictorialism and modernism.

When I met him he accepted to not only have a chat about Camera Obscura, but also to explain in detail the technical procedure he uses, which had raised my curiosity.

Fabiano Busdraghi: How did you start to take photographs? What’s your story as a photographer?

Samuele Piccoli: First of all I think I am more of an experimenter, rather than a proper photographer. I don’t want to limit myself in any way, so until possible, I want to escape the trap of definitions and categories.

Nevertheless, my story begins in the most classic of ways: around the age of 18 my uncle gave me an old, completely manual Russian reflex. I perfectly remember the joy I felt as I experienced placing images in focus, and that first experience opened up a whole new world for me. I then began my “career” as a classic lover of photography, inspired by shots in the National Geographic, until I had the extraordinary pleasure of meeting someone who opened my eyes on the ability of photography to look into your soul. I discovered a new world, all my preconceptions fell, my certainties crumbled, and all canons were overturned. The photographs became mine, whether one liked it or not.

Fabiano Busdraghi: How was your series of photographs/photocopies born?

Samuele Piccoli: It was a slow evolution, but it all goes back to my passion for the pinhole images. This miraculous instrument of expression (one should glorify it) allowed me to appreciate the work of Paolo Gioli, to discover the wonderful world behind polaroids, and most of all, to begin to experiment in a new discipline (that of polaroids) which was for me completely new.

One afternoon I was taking a pinhole macro polaroid of a rose, and as I was about to tear the negative from the positive, as usual, I realised that the movement wasn’t new to me. In fact it wasn’t. I had repeated that simple and dull movement hundreds of times, during my years in primary school. In fact we would often use acetone to transfer images from magazines to drawing paper, to later draw around them. When the acetone was dry, the parts of the magazine were then torn off just as you tear off a Polaroid. A simple and marvellous act, all in one.

This opened up an infinite number of new paths to follow, and I was thrilled, to say the least. However, the project was only at draft level, I had discovered the technique but had to find the message that suited the procedure best. Instinct and passion did the rest of the work.

A part from photography, I am an admirer of painting, and in that same day I was struck by a portrait by Sergio Flori and a photo by Claude Cahun very similar to a photocopy, and the epiphany occurred. I started to select various subjects from my archive, I photocopied them and transferred them on drawing paper. The results were encouraging, but too complacent. One day I found myself in front of a piece by Araki, I observed it, studied it, admired it. That technique gave me the courage and I finally decided to violate the last of seals: the sacredness of emulsion. From the overcoming of the last barrier, free from all conditionalities, I created these photo(copie)s.

Fabiano Busdraghi: This return to a gesture that belongs to your childhood, a sort of memory that remained in the movement of your hands, is very interesting. Can you expand on this subject?

Samuele Piccoli: I admit that I like to go against the tide, I don’t reject modernity a priori, I’d be crazy, but I love to use my hands, and not only the index in my right hand. I find great satisfaction in building what I need with the few tools available in my garage and with the help of others.

Maybe no one thinks about it, but I often realise that I tend to ignore the senses (tact and smell) because of the speed, but also the superficiality, with which we are forced to live. I am often in a hurry even while dedicated to a hobby, and most of all, I don’t stop to see the panorama that I’ve left behind me.

Facing such a paradox, when I have some free time, I’ve chosen to make it truly mine, “I have so many things to do? Bollocks”, and magically, I have the chance to stop, reflect, and look back.

Fabiano Busdraghi: In your own photos we can see a long manual work of enrichment of the images. For the common sense of most people, your images are in fact not “actual photographs”, but a mix of drawing, collage, transfers, very distant from pieces belonging to the photographic category.

f you’ve read my series of articles on photography and truth you’ll know that for me, it’s a misguiding affirmation. How do you confront yourself with this issue? Do you think that photography is clearly definable? Is every kind of liberty allowed?

Samuele Piccoli: I’ve carefully read the articles on Camera Obscura because, living in close contact with other photographers/lovers of photography, I find these to be the most controversial and debated topics. To answer your question, we necessarily need to take a conceptual step back. To better explain myself, I’d like to tell share a zen story which was very dear to Tiziano Terzani.

A knowledgeable professor goes to see a monk and asks him: “Tell me, what is zen?”

The monk doesn’t reply, and instead invites him to sit down, places a cup in front of him and begins to pour some tea. The cup fills up, but the monk keeps on pouring. The professor is confused, remains silent for a while, then as the monk keeps on pouring, he warns him:

-It’s full, it’s full!

“Yes!” replies the monk. “You too are full of opinions and prejudices. How can I tell you what zen is, if you first don’t empty your mind?”

I’m perfectly aware of the fact that what I said does not in any way solve the various philosophical disputes, but why limit oneself? Why close oneself up in a definition? A discipline which is structured and moves only inside immutable schemes can only be a science, it cannot be called art.

Realising technically exceptional photographs is not my preferred means to transmit an emotion, to transmit a state of mind. Don’t misinterpret this, I love photographers who need a certain kind of paper to obtain a certain tone of white or range of tones, they’re the same tricks I use. I also admire those who, while shooting, already know where to place a mask when in front of the enlarger.

However, I’m not like that, I want to be different, I have to be different, and to do this, technique is not enough. I want that a single brush stroke of emulsion, applied imperfectly, makes the photo unique, unpredictable, dreamlike. That’s my aim. Unique and dreamlike, my photos should be that. Volumes should disappear, perspectives get overturned, the exposition should disturb, the “stop image” be non-existent, movement be light. In this search for a dream-like state, what changes, if the means of acquiring the image is a sensor, a Polaroid or film? Without photography my portraits would not make sense, and we wouldn’t be talking about this now.

Fabiano Busdraghi: I’m a great admirer of Tiziano Terzani, I’ve basically read all of his books, I’d read that story but had forgotten it. Thanks for having reminded me of it! As for the rest, I completely agree with you, why limit ourselves to a definition when what counts is really the creation of a piece?

But let’s get back to our article. You have generously accepted to share your technique on Camera Obscura. What procedure do you follow to obtain your photo(copie)s? Can you describe your technique in detail?

Samuele Piccoli: I’d like to clarify that the procedure itself is very simple and the materials are readily available. However the result of the transfer is never homogenous, a lot of factors define the final result, such as temperature, the pressure applied on the photo, the type of “chemical” used to transfer the image (acetone or cleaning fluid), not to talk about the paper you use and the speed with which you tear the photo once it’s dry.

Let’s proceed in order. I think we should start with the mechanical process and then get into detail about the materials. I would start by distinguishing the transfers according to the kind of “transfer chemical” used (acetone or cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene).

The classic transfer (with acetone) requires you to place the “emulsion” of the photocopy on a piece of drawing paper, then soak a cotton ball, and brush vigorously the back of the photocopy with the cotton ball. You then wait for it all to dry and then carefully separate the two sheets, that have adhered to one another as they dried. The result of this process is an image with a dominating pink tone, very soft and with a significant and inhomogeneous loss of detail. All these characteristics give the image an effect which is very ‘800.

Now let’s look into detail at how we can work with all the variables involved, so as to control the process as much as possible.

Acetone transfert

There are various types of acetone on the market, the most common is the one used to remove nail polish. It leaves a dominating tone of pink, which I find pleasant, but if you would rather not have such a result, you should use the cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene technique.

The photocopy (negative)

With the classic process I was only able to transfer black and white photocopies. I made several attempts with colour photocopies obtaining no result. This probably depends on the kind of pigment used by the photocopier, so I wouldn’t exclude the possibility of transferring colour. I should clarify that not all the image in the photocopy will transfer, and softer tones are often lost or blurred. I would advise the use of photos with strong contour lines.

Transfert paper (positive)

The detail in the final photo depends heavily on the degree of roughness of the surface of the paper which will hold the pigments of the photocopy. Obviously, this depends on the result which we want to obtain, but generally, the smoother the paper and the more the transfer will give detail to the final photo.

Often parts of the negative remain attached to the positive, with the serious risk of having to throw away everything. To try and minimise this risk, for the positive I use paper with a weight of at least 80grams, which allows me to use acrylic colours with little worries.

The pressure on photocopy back

The pressure of the cotton ball on the back of the photocopy is directly proportional to the level of detail of the final photo. The pressure applied will obviously never be uniform throughout the photo, but you can use a roller to homogenise the effect.

The transfer with cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene involves a slightly different procedure. After various attempts, I think that the best method is to apply a sheet of paper (your future positive) which should not be too heavy (photocopying paper is best) on the photocopy (the negative), and apply a first layer of cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene with the same cotton ball, on the back of the positive. Then lift and reverse the negative and positive couple of sheets, and apply the fluid with the cotton ball on the back of the negative. After waiting for a few seconds, proceed with detaching the negative from the positive. This way you avoid possible partial detachments of the negative. The result is a significantly soft-toned unsaturated photo, with a notably higher level of detail respect to the classic method. Even in this case, let us look at the variables of the procedure.

Trichloroethylene transfer

The Trichloroethylene fluid/trichloroethylene is much cheaper than acetone, but is also more toxic. It doesn’t leave any dominant colour tones on the final photo.

The photocopy (negative)

With the cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene process I was able to transfer both black and white and coloured photographs. On a sheet of paper of the same smoothness, respect to the classic method, the cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene process has the great advantage of transferring more details. Thus there aren’t serious limits on the characteristics of the image to copy.

The transfer paper (positivo)

The notable limit of this technique is that it is only possible to transfer images on paper of low weight. During the first brush stroke on the back of the negative, if the paper is too thick, the cleaning fluid/trichloroethylene does not successfully effect the positive.

As with the classic method, the same rule is valid: the smoother the paper, the more detail will be transferred to the final photo. The transfer is in fact based on the contact between negative and positive, and on the pressure applied with the cotton ball. A rougher paper, having more texture, is a significant obstacle to the correct contact between the paper and the relative transfer.

This significantly limits the post-production phase.

Fabiano Busdraghi: How do photo(copie)s perform, when it comes to the conservation of such images? Do you believe that the stability of an image in time is important or is an ephemeral and variable material even more interesting?

Samuele Piccoli: Technically, all that is needed is a simple protective spray for mixed means. However, I don’t want to use anything for a series of reasons: firstly because I’m curious and have no idea of how these images will evolve in time, and secondly I find it very instructive to have an object that, with its very own existence, reminds me that everything is transitory. In my office I have a photo printed years ago with fiber paper that, slowly, day after day, is getting darker, changing. A bit like all of us.

I find this all very beautiful.

Do you have any favourite online magazines or blogs regarding photography? Do you think that they could substitute the distribution of images in classic venues?

Samuele Piccoli: As I mentioned before, years ago I had a subscription to the National Geographic, but my taste now has changed and I’ve not renewed it. I like to read ‘Arte’, but this magazine is also converting (or it already has) to the religion of marketing, with more and more gallery artists and less technique and expressivity.

The internet is surely an important and fundamental resource, but I don’t think that it could substitute classic venues for the distribution of images, or at least it won’t until materials will still have a certain importance in the world of photography. I’m preparing an exposition of pinhole photographs printed on watercolour paper, uniting the evanescence-pinhole duality with the imperfections of the printing process. This makes the photos appear surreal, and seeing them on video would be pointless.

Fabiano Busdraghi: Tell me of a photographer whose work you enjoy, and why.

Samuele Piccoli: I deeply enjoy the work of Filippo Basetti, firstly because he is a delightful person, and also because he is a multitalented artist, open to all forms of expression, and he helped me a lot while I was seeking my own style.

Fabiano Busdraghi: Just a few curiosities on your personal tastes. What book are you currently reading? What kind of music do you listen to? What are your favourite films?

Samuele Piccoli: I’m reading Brida, by Paulo Coelho. Many might find it very mainstream, but I don’t care. Although the book that truly made me dream is “Siddharta” by Herman Hesse.

I enjoy listening to Lucio Battisti, Francesco De Gregori, Fabrizio De Andrè, and I’ve recently discovered Bandabardò. I’ve also discovered a passion for classical music.

Regarding films, it’s a tie between “Das Leben der Anderen” by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck and “The man who wasn’t there” by the Coen brothers.

Ciao Sammuele… mi interessa molto la tecnica della triellina avendola affrontata pure a scuola ma solo su carta… volevo chiederti se è possibile fare trasferimenti anche su altri materiali come legno, plexliglas? Ovviamente cercando di ottenere più o meno lo stesso risultato… se nn è possibile esistono altre tecniche che lo permettano?

grazie

Ciao, ho fatto delle prove su vetro, plexliglas, polistirolo, cartone e legno. La tecnica, basandosi sullo “scioglimento” del pigmento della foto grazie al solvente (trielina) e relativo trasferimento su un altro materiale, ha dei risultati diversi a seconda del grado di porosità e ruvidezza del supporto che accoglierà la foto. Essenzialmente tutti i materiali posso accogliere questo pigmento. Per esperienza ti posso dire che sul vetro si ha una notevolissima perdita di dettaglio ma il pigmento ti viene restituito con un effetto a “puntini” molto pittoresco, Sul legno ti puoi scordare l’immagine originale, idem per quanto riguarda il polistirolo. L’effetto più sorprendente si ottiene con il plexiglas, perchè praticamente restituisce quasi l’intera scala tonale, non si ha una perdita eccessiva di dettaglio, e su tutta la foto si forma una stana velatura tipo “figurina panini staccata da un vetro dopo 10 anni”.

Ciao Samuele,

ho una domanda: hai per caso fatto la prova della tecnica della trielina anche con la tela?

ti spiego: mi è tornata in mente questa tecnica imparata alle medie perchè volevo trovare un modo abbastanza veloce, ma allo stesso tempo di effetto per riportare delle immagini stampate su normale carta da stampante, magari in maniera speculare in modo da tornare ‘dritta’ sulla tela di immagini tipo quadri o icone per dare l’aspetto artistico..

Che dici, può funzionare con tela per fare piccoli quadretti con immagini di quadri più famosi o pensi che perda troppo?

un saluto e grazie

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.