Text and photos by Marc Erwin Babej, surgeon’s notes by Maria M. LoTempio.

Mask of Perfection focuses on the complex and ambivalent relationship between the beauty we perceive subjectively on the one hand, and the plastic surgeon’s scientific, geometry-based standard of beauty on the other.

Specific beauty ideals have seesawed over the course of history, but its fundamentals have remained consistent. Evolutionary psychology has demonstrated a high degree of consistency at the root level of perceptions of beauty (such as clear skin and a waist-hip ratio around 0.7). Accordingly, notable shifts in perceptions of beauty have been rare.

What’s more, they coincide with discontinuities in general history, and particularly art history. The Renaissance marked a shift toward sleeker body ideal, prizing a sleek figure and flattened chest. The Baroque became synonymous with a body type we describe to this day as Rubenesque. Following the end of World War I, changes in the social order led to the idolization of a slim, more androgynous female body type, epitomized by Hollywood stars such as Louise Brooks.

The current change in beauty ideal, however, is more profound than any that preceded it – in both kind and degree. In the past, manifestations of a beauty ideal could be discovered in the flesh, and also represented in art. They were also concretized and rationalized by experts on the subject (think of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man). But any individual’s conforming to the ideal of the time was a matter of “god-given” gift.

The currently emerging ideal of beauty is unprecedented in that it is actionable, and that conformity to it has become widely available. Lips like Angelina Jolie; breasts like Scarlett Johansson; a butt like Kim Kardashian; less slanted eyes like a white woman; a wrinkle-free complexion like a cosmetics model? Available at a plastic surgeon near you. In other words, the emerging beauty ideal not only reflects changing taste, but also represents a radical shift in the understanding of beauty itself. Conformity to an ideal of beauty used to be a daydream; now, it has become a line item on a shopping list. Whether this development is liberating or cheapens the concept of human beauty (or both at the same time) is a matter of individual judgment.

Hand in hand with these changes in kind and degree goes a change in the mode of propagation: as more and more of the most prominent figures in contemporary society (celebrities, media personalities; increasingly also “serious” figures like politicians) are being adjusted by plastic surgeons to the scientific standard, the standard itself is influencing the way the general public perceives who and what is beautiful – and which parts of their own bodies members of the general public might consider to have altered.

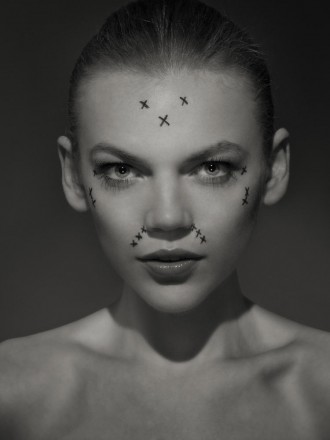

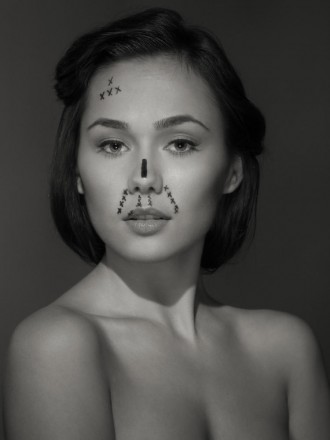

Mask of Perfection literally superimposes the emerging scientific standard on the subjective view of beauty – and reveals the discrepancies and tensions between the two. To achieve this, renowned New York City plastic surgeon Maria M. LoTempio, MD and I selected twelve women in their Twenties who conform to the natural standard of beauty (“the last people who’d ‘need’ any work done”): they are young, highly attractive, and don’t have any particular feature that would call for alteration.

Casting for this series was a very interesting process: to look “like the last person who needs work done,” the models had to be attractive in a specific way: they couldn’t have a feature that was out of the norm for their ethnicity. They couldn’t have had plastic surgery before; they had to represent a range of ethnicities and different looks. At the same time they had to come off as individuals, with personalities that project in an image (my focus in casting). And of course they had to have things for Dr. LoTempio to “perfect”.

There was actually one model we had to turn down because she was perfect by the standards of plastic surgery. She really wanted to be part of the project and I thought she’d be great, so I found myself in the paradoxical situation of begging Dr. LoTempio to find some flaw in her. To no avail.

Dr. LoTempio was then given the assignment to do what it takes to “upgrade” these “patients” according to the standards of her profession. All patients were initially evaluated via a set of five clinical images (frontal, 3/4 and full profiles on both side) and then examined in person. Finally, they were marked with pre-operative markings – the Mask of Perfection. The images in this series were taken in this state.

The style of representation is as important to this series as the time. All along, my goal was to prevent knee-jerk “for” or “against” reactions, and instead to inspire individual reflection. This is achieved by layering two alienation effects: The markings “mar the view” of the subjects, preventing viewers from immersing themselves in their natural beauty. Meanwhile, the romantic, aestheticizing style of 1930s Hollywood portraiture was chosen to bar viewers from overly identifying with the plastic surgeon.

Achieving an authentic 1930s Hollywood portrait look was essential: rather than use soft boxes and other soft light sources, we used the same equipment as Hollywood photographers of that era. The main light was a Fresnel light – essentially a stage light that can be adjusted in size, has no “hot spot” and can be focused like a lens. We consistently used a butterfly lighting setup, which was commonly used in portraiture of female Hollywood stars of the era. The main light is positioned frontally and shines down on the model from as high as 4m, to place a shadow under the nose. A secondary light shines from below, to soften the shadow.

The right kind of retouching style was another crucial aspect of the 1940s Hollywood look. Luckily, I found a true master of his art in Irfan Yonac – a former fashion photographer who is old enough to have retouched in the pre-digital era and is an expert in the look of that era.

For more photos and stories, please visit Marc Erwin Babej website.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.