Text and photos by Jonathan Morse.

People sacrifice for their tickets to the Hawaiian Islands. They plan the expensive vacation carefully, and by the time they board the airplane they have prepared themselves with cameras. Then the airplane lands, the cameras are deposited in rental cars, and their owners begin passing through the islands, one beautiful view at a time. Everywhere they stop they take pictures.

But after the airplane lands they discover that pictures were waiting for them all along. Professional photographers have already held sittings for all of the beauty, and whatever the tourist sees he’ll see belatedly. So far as the tourist is concerned, though, that’s all to the good. When she buys her photosouvenir she’s entering into a contract with it to learn to see the Islands in the proper souvenir way, and after she gets back home to the cold the contract will fulfill itself. From then on, memory will be a mediating image between the tourist and the islands. Trained by the souvenir, it will have become photographic.

But is it possible to retain the unphotographic part of memory? The experience that once included you the seer herself in the act of seeing?

Perhaps. Now that you’re looking at my souvenir image yourself, you might try the experiment of lifting your eyes from the monitor and thinking about your expectations. You came to Hawaii because you’d been told to expect blue ocean under brilliant tropical sun, and that is what you’ve found. But in the airport or at the hotel you also picked up a free magazine full of pretty advertisements, and now that facilitator of commerce is reassuring you that the deep blue and the intense light around you are merely illustrations of the real paper thing in your hand. You won’t become aware of the blue and the light, either, until you eschew the printed matter. Another name for that vision combined with memory but separated from commentary is art, and you won’t be able to experience the blue and the light until you’ve helped art teach you to look before you grant the pedagogical commentary its preliminary hearing.

One of the early lessons, for instance, might be a demonstration that the interaction between art and the world is an interaction between a brush full of light and a canvas full of not yet painted dark. If you let the light teach you that the sunny ocean before you is also a vessel full of darkness, you’ll realize that there’s a dark complement to the sun-soaked pages of your tourist magazine. Under the brilliant sun, look for that dark. It will help you see the light that emerges from dark depths.

To see light on an island where all is light, look for the dark. That dialectic is at work at all times in every part of the visual field. It governs the way we perceive scale, for instance. On this tiny island, light is vast on the small scale as well as the large, and even a tiny maneuver in the light (say, a butterfly floating its colors toward a flower) can reveal the vastness in a new way: butterfly and plant, orange wing and red stamen, green leaf absorbing the sun and gray eye reflecting it back to us. Then, in the reflected glow, we can feel our own eyes grow warm.

Or color – even the sunny palette of that tropical tourist cliché, the bird of paradise plant – can reveal its kinship with shadow. In the image below, the shadow’s white matrix was a piece of styrofoam which once protected a TV in a shipping carton. Repurposed as an image, the foam promptly got busy being white, and its whiteness induced flat black shadow to bring forth a living form repeating itself in jagged orange and curved blue and round green. Suddenly, as we looked, a kinship established itself between the flower here and the flower-colored butterfly elsewhere on the ground.

In his essay “Art as Technique,” Viktor Shklovsky called that process of seeing anew “defamiliarization.” Art defamilarizes, said Shklovsky. It breaks down familiar categories (such as “flower”) into their unfamiliar elements (shape, color). As Shklovsky put it, “Art removes objects from the automatism of perception.” If you defamiliarize the imaged shadow below, for instance, even in the simplest way (for instance, by turning it upside down), its repurposed darkness will suddenly acquire the power to still color and movement. Two inseparable attributes of life will detach themselves from their origin in sun and water and display themselves as shadow images of a plant form that is undying because it has never lived. Yet at the bottom of the dark flat shadow, a round, sun-warmed stem lives on.

© United States Postal Service.

It lives on in a changed way, too, as if it had been made the subject of a myth: a fiction that compels us to believe in it despite ourselves. I think of my hands, for instance, in an intimate way, as a fundamental part of what I am. Though I’m changing on my way through life toward death, I can’t make myself stop thinking I know that my body parts always have been the same, always will be the same. But under the sun of Hawaii, where hands can become as green as trees and then begin to impose light onto shadow keyboards, some of our certainties can at least begin to revise themselves into new mythologies. In English-speaking countries there used to be a single fantasy crayon color called “Flesh,” but under the warm sun our notions of the fleshly are set free to root themselves and grow more generously in other zones of the spectrum.

They can go white, for instance, when the dawn begins shining through them. Then an idea of ascent becomes almost namable in body language. Dancers articulate that language too, but for them the terms of the naming are always bound to the dark earth.

Bound to the dark earth, we human beings have trouble looking up. Wherever we are, we have to keep our eyes on the road. After the tourists have made their descent and landed in Hawaii, they step into rented cars and resume the same road experience they had when they drove to their airports of departure. But a nice thing about certain roads is that they intersect the course of light in unexpected ways. If you’d like to monetize that intersection for the needs of a tourist economy, you could give it a name like “Hawaii.” But it’s really about shapes in the light, anywhere.

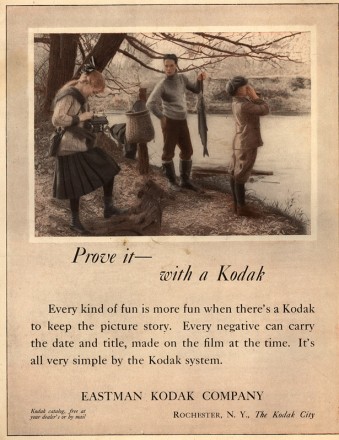

Teaching us that truth about light and form may be what photography does best, despite all its efforts not to. If she were interested in image only as an illustration of some words, a tourist a century ago could buy what was called an autographic camera and write captions onto an image at the instant she perceived it. “Prove it,” said the camera manufacturer to the tourist, and then it sold her a piece of technology to convince her that she had proved it. “I was here,” said the autograph written into the picture – and “here” could be given a place name and a set of coordinates in memory’s geography.

But what can you call the instant when ground and air and form and light all come together within an image frame? That coming together proves nothing; it only exists for an instant, then goes back to wherever it came from. But instants are all that photography is about. In the image of an instant there’s a mode of vision that exists independently of the postcards marketed as aids to memory. What is remembered and what has been seen are not the same, and once in a while there will come an instant to prove that to us.

And then we’ll know we’ve entered the presence of something that has been seen in spite of all the laborious camera business that preceded the seeing.

Please visit Jonathan Morse for more photos and stories.

You can also subscribe to this post comments RSS feed.